Welcome to our virtual exhibits page!

An Introduction to Trench Art:

The Story of AH Yorton

By Allie Krisko

What is Trench Art?

In his book titled Trench Art (second edition), Nicholas J. Saunders defines Trench Art as: “…Any object made by soldiers, prisoners of war and civilians, as long as object and maker are associated in time and space with armed conflict or its consequences.” As a concept, Trench Art has existed throughout history. Soldiers have probably always created some form of object to pass the time or to have some sort of souvenir, but due to the materials they used and the amount of time passed since creation, not many of these older items were able to survive into modern times or are unable to be recognized for what they are. The industrialized nature of World War I, and the amount of people directly impacted as both soldiers and civilians, allowed an explosion in the number of pieces created out of material that will last lifetimes. This close association with World War I, and its iconic trenches along the western front, made “Trench Art” a natural name, and one which would then be applied to all such items.

Trench Art takes a variety of forms. The most frequently encountered item is the decorated artillery shell, but other common pieces include ashtrays, matchbox holders, lighters, inkwells, letter openers, and jewelry. To create a decorated shell, the first step was to select the canvas by testing the shells resonance – a faulty shell could break and the work would have to be abandoned. Next, something was used to fill the shell to provide resistance for the artist to hammer against. Though there were a couple of options, the one that worked best was lead. The heat of liquid lead poured into a shell casing made it more malleable, and once cooled the resistance was perfect for even the most intricate designs to be punched in. After the work was completed, the lead could be reheated, poured out, and reused again and again. To get the perfect designs on the shells, templates would be tied onto them using twine so the creator would know where to hammer. Simpler designs could be free hand pinned into shells without templates, and would sometimes be completed with lines drawn to connect the dots.

During World War I soldiers were rotated in and out of the trenches, usually staying a maximum of two weeks before being sent behind the lines. Soldiers close to the fight were able to make pieces of Trench Art, but they would be simpler items such as rings made out of aluminum, wood/chalk/stone carvings, embroidery/textile paintings/beadwork, or simple designs pinned or scratched into their mess kits or artillery shells.

The more elaborate pieces that soldiers made were completed behind the lines in relative safety and with access to more tools and machinery. Civilians began their Trench Art trade by creating souvenirs for soldiers during the war, which flourished into a booming cottage industry between World Wars I and II. Everyday items like lamps and candle sticks were of course practical for everyone, and more tailored souvenirs could be made for those making pilgrimages to visit specific battle sites or towns. Some businesses even offered services where they would take war material provided by the customer and either mount them for display on a piece of wood or marble, or create useful household items, such as dinner gongs, clocks, or cups, out of the objects. After World War II, especially with more modern technologies for fighting and entertainment purposes, the practice of making Trench Art became less common, but pieces connected to more recent wars can still be found.

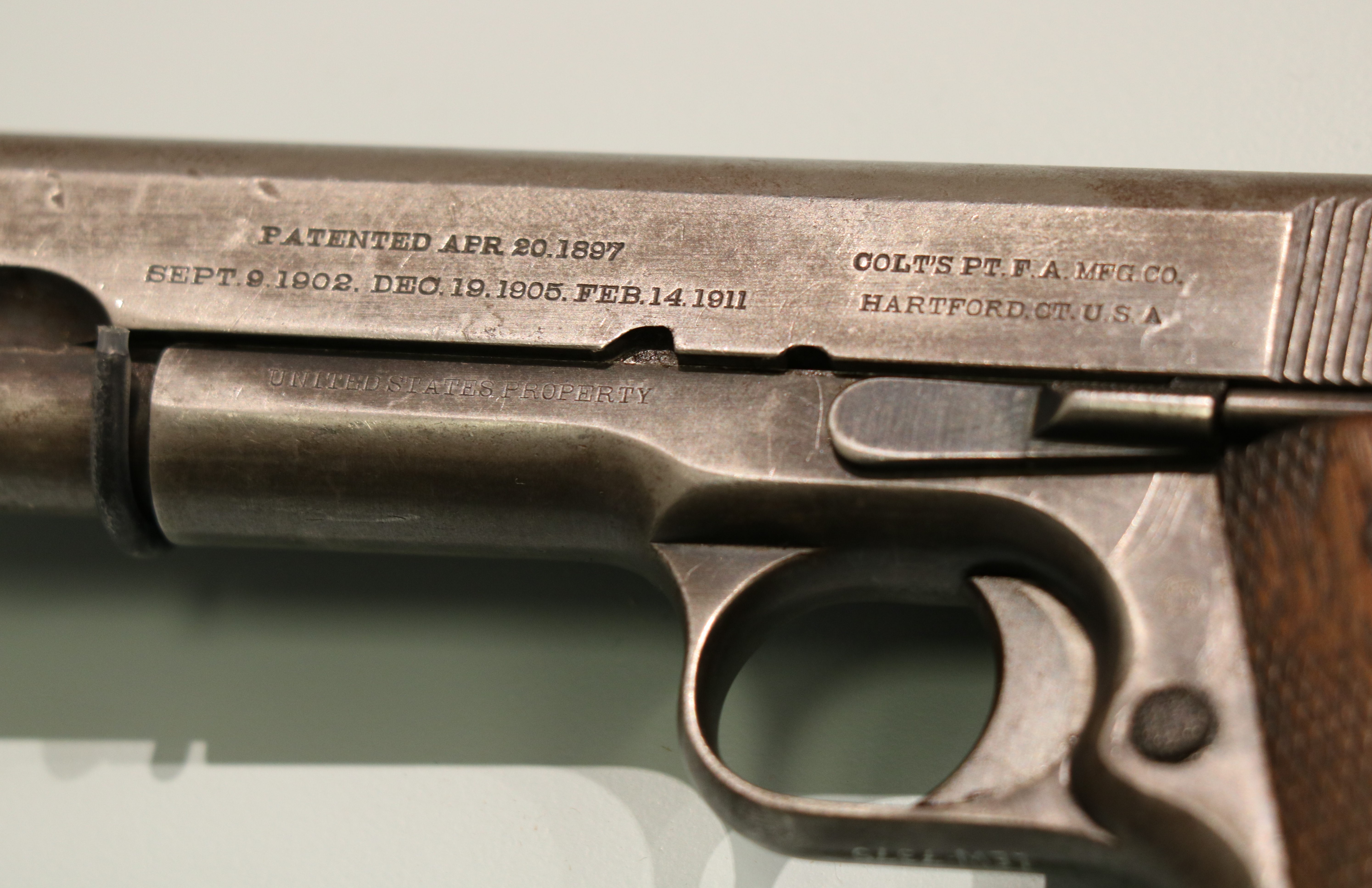

What shell was used to create the A.H. Yorton Trench Art?

Headstamps are located on the bottom of most shell casings and provide information related to its manufacture. The A.H. Yorton shell headstamp reads “Remington UMC; 75 DEC; SM; 92L4 16 C.” This indicates that the shell was manufactured in 1916 lot# 92L4 by Remington UMC for the French 75mm Field Gun. The SM is most likely an inspector’s mark, and is probably the initials of the inspector.

Founded in 1867, UMC was a manufacturer of small arms cartridges. They merged with Remington Arms in 1912, and together they became a major arms supplier during World War I. Headquartered in Bridgeport, Connecticut with a factory on location, they manufactured ammunition until 1970. The Connecticut factory complex was completely vacated by 1988.

The French 75mm Field Gun was initially adopted in 1898. During World War I, they were initially used as anti-personnel weapons firing time-fused shrapnel shells. As the war ground on high-explosive shells became more common, and toxic gas shells were also developed. Additionally, some guns were modified to allow use as truck mounted anti-aircraft artillery or armament for tanks. Designed with unprecedented technologies for the time, the French 75mm was able to fire without needing to be re-aimed after every shot. This allowed for rapid firing, and a good crew could reload and fire 15 rounds per minute, and a highly experienced crew able to fire up to 30 for a short period of time. These guns had a range of about 5.3 miles.

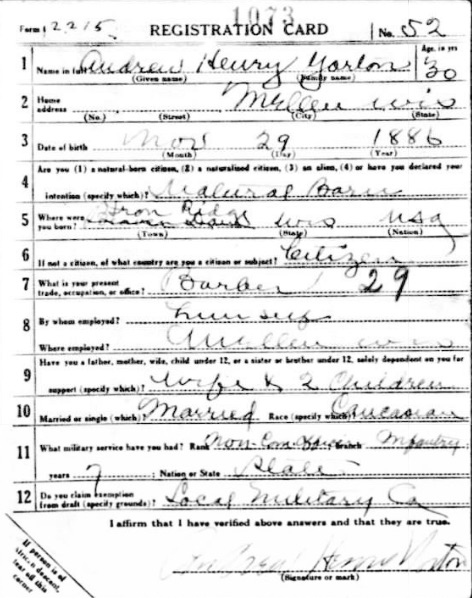

Who Was AH Yorton?

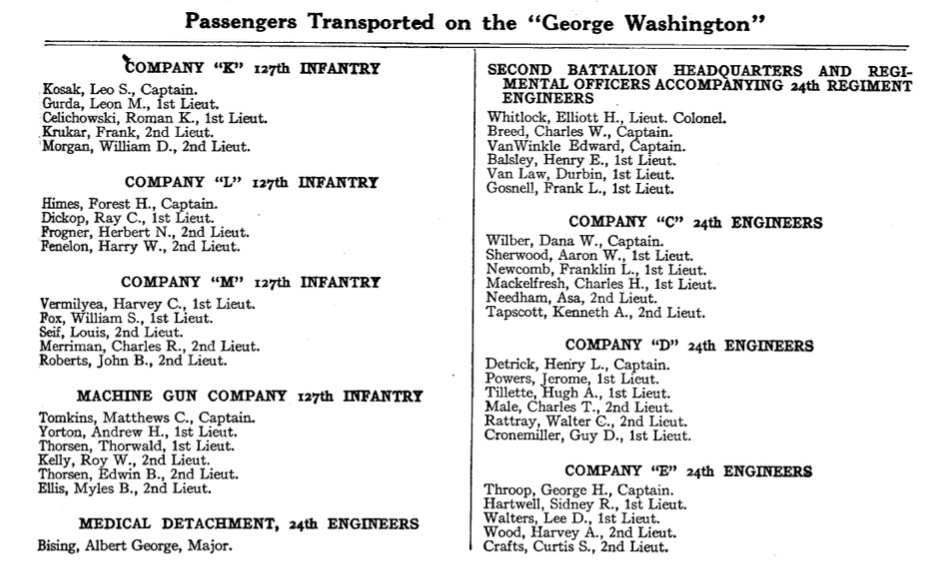

Andrew Henry Yorton was born November 29, 1886 to Morris Yorton and Matilda Marie Louise Stolle, and he married Melina Eva B Cyr on November 14, 1905 in Ashland, Wisconsin. Andrew was a 1st Lieutenant in Company C of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment of the Wisconsin National Guard. During World War I, Andrew’s unit was called into service and merged with other Wisconsin and Michigan National Guard units to form the 32nd Division. He was placed into a machine gun company in the 127th Infantry with Captain Matthews C. Tomkins, 1st Lieutenant Thorwald Thorsen, 2nd Lieutenant Roy W. Kelly, 2nd Lieutenant Edwin B. Thorsen, and 2nd Lieutenant Myles B. Ellis.

Members of the 127th Infantry boarded the USS George Washington on February 18th, 1918 and, in convoy with the USS President Grant, Covington, De Kalb, Manchuria, Pastores, Susquehanna, and El Sol, they began their cross of the Atlantic Ocean towards France. Upon arrival in France, the 127th Infantry was initially assigned as a temporary labor troop, completing projects in the Service of Supply – mainly constructing supply depots. On May 21, 1918, the date listed on the Trench Art piece, they entered the trenches in the Alsace sector for the first time.

On July 30, 1918, the 127th saw their first major offensive action at the Bois des Grimpettes. Though stalled by German machine gun fire, they soon established themselves at the edge of the woods. A counter-attack by the Germans was launched at night, resulting in a bayonet melee that raged for hours before the Germans were finally repulsed. Unfortunately, Edwin Thorsen from Andrew’s machine gun company died of wounds he sustained in action on August 2, 1918. He is buried in the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery.

September 5th saw the 32nd Division transferred to the First American Army, initiating their withdrawal from the Oise-Aisne Offensive. In recognition for actions of the units before the the transfer, General Mangin awarded the division the Croix de Guerre with Palm. The units of the 32nd Division were the only National Guard units to be bestowed with this award during World War I. The Croix de Guerre, or Cross of War, was created in France in 1915 and was commonly awarded to foreign forces, individual or units, who were allied to France for acts of heroism during combat with the enemy. The Croix de Guerre with Palm was issued to units whose members performed heroic deeds in combat and were later recognized by headquarters for their actions.

At some point during, or shortly after, the war, Andrew wanted a physical representation for the day he entered the trenches with the rest of the soldiers of the 127th Infantry. It is unknown if he created the shell himself, if he obtained it from a fellow soldier, or if he requested a personalized souvenir from a civilian artist. Whatever the origin of the Trench Art, it is a work of art that holds the history of not only a time and place, but also an individual that served his country and survived what may have seemed the impossible.

Andrew died on May 27, 1959 in Kenosha, Wisconsin at the age of 72. How his Trench Art made it from his home in Wisconsin to an antique store in Georgia is a mystery, but the history it contains will live on for many years to come.

Pointe Du Hoc

2nd Ranger Battalion in World War II “Rangers Lead the Way”

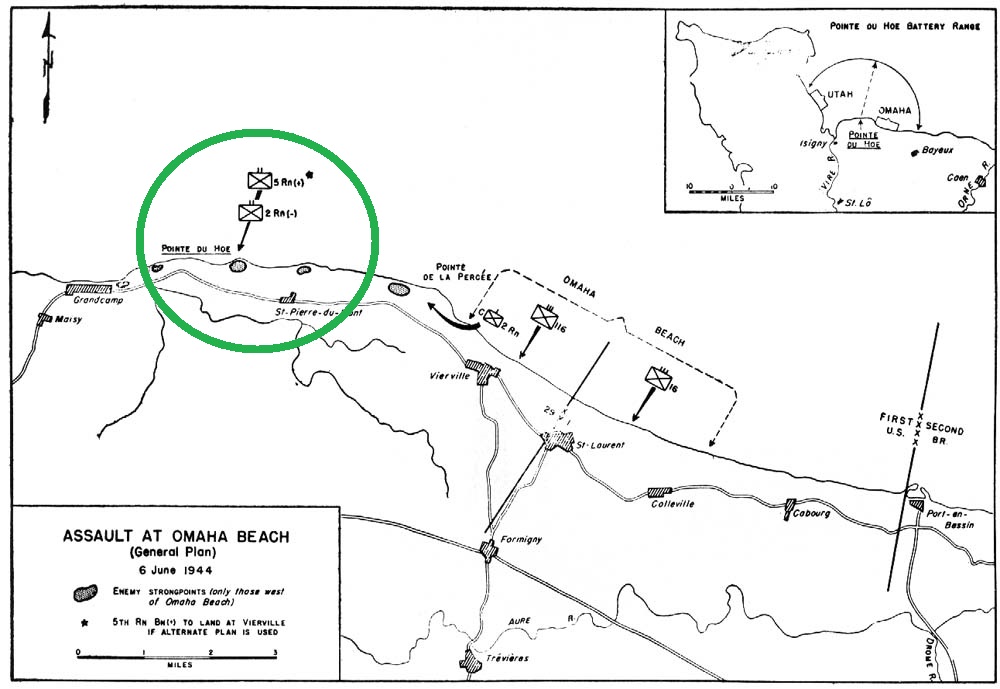

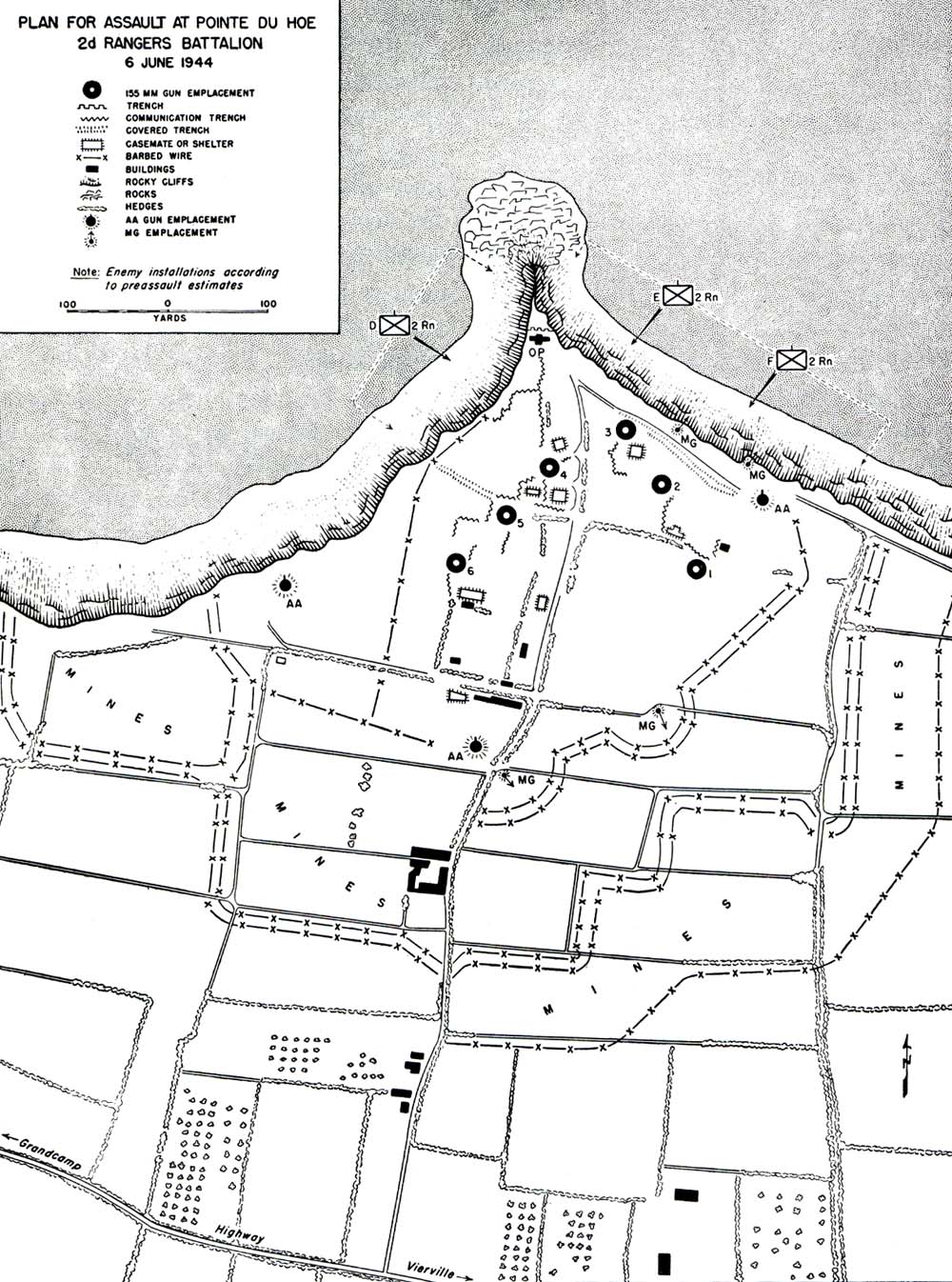

In one of the most celebrated events in World War II, the Rangers of the 2nd Battalion scaled the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc in the face of heavy German resistance. In spite of machine gun and small arms fire, as well as German grenades and mortar shells, the Rangers scaled the steep cliffs using ropes, grappling hooks and metal ladders. The Rangers of the 2nd Battalion captured and disabled a German battery of 155mm cannons which were trained on Utah Beach. This action, no doubt saved many American lives during the landing.

The Normandy Coastline and Pointe du Hoc

These maps show the German defensive positions on the rocky heights of Pointe du Hoc which were a dangerous threat to the success of the Allied landings on the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944. The Rangers of the 2nd Battalion were given the mission of scaling the cliffs and eliminating the enemy threat to the landings.

Principle of War: Surprise

The German defenses around the Pointe du Hoc coastal gun batteries were oriented inland as the most likely avenue of approach. It was believed a frontal assault up the point’s cliff face would be impossible, therefore that is precisely where the Rangers chose to strike.

Principle of Sustainment: Simplicity

The Rangers would be assaulting the point from small amphibious landing craft and carrying all necessary supplies with them up narrow ladders to the top. Immediate resupply could not be guaranteed. The mission dictated that sustainment be minimal and simple.

Terrain Analysis: Avenues of Approach

The Germans believed an attack must come from inland and oriented their defenses accordingly. The Rangers therefore chose their avenue of approach as that which as least defended.

Army Rangers

The 2nd Ranger Battalion was formed in September 1943 and was sent to England to prepare for their role in the invasion of occupied France. In England, the Rangers conducted rigorous training for their mission to scale the cliffs on the Normandy coast. Their training was tested on June 6, 1944.

On 6 June, Dog, Easy, and Fox Companies of the 2nd Battalion crossed the English Chanel and landed at the base of the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc in Normandy, France. The Rangers, led by LTC James Rudder landed in modified amphibious landing craft called “Ducks” (DUKW), operated by personnel from the British Royal Navy.

The capture of Pointe du Hoc, on the coast of Normandy, is one of the most dramatic actions of World War II. The Rangers of the 2nd Battalion scaled the cliffs under heavy German fire and defeated a well-entrenched enemy force. Their bravery and dedication earned the US Army Rangers the gratitude and respect of the entire nation.

Since 1974, the 2nd Battalion, 75th Rangers have made Fort Lewis their home. They are often deployed to “hot spots” throughout the world in their mission to defend America and her allies.

The 3rd Infantry Division in World War II at Anzio: “Rock of the Marne”

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the focus of the American public was on the punishment of Imperial Japan. However, after the declaration of war on Japan by the United States, Germany, an ally of Japan, declared war on the U.S. This was to prove disastrous to the Third Reich. As American war leadership studied the situation, in consultation with other allied nations, it was determined that Nazi Germany was a far more dangerous threat than Japan. Germany had the power and technology to potentially win the war. As a result, the United States Army was committed to send more troops to the war in Europe than any other theater of operations.

The 3rd Division served on the Western Front in World War I, where they earned their nickname “The Rock of the Marne.” The headquarters of the 3rd Division arrived on Camp Lewis in 1921 and the Division trained on both the post and the local area. Their training including amphibious landings on beaches along Puget Sound. This training would prove incredibly valuable during World War II.

The 3rd Infantry Division was one of the most battle tested American Divisions when it landed on the Anzio in January 1944. Prior to Anzio, the Division had fought in North Africa, Sicily, and Salerno, Italy. The fighting at Anzio proved to be some of the most vicious of the European Theater when crack German units were sent to oppose the American advance.

The 3rd Infantry Division landed at Anzio, Italy on 22 January 1944 and met determined resistance from veteran German troops. This resulted in four weeks of fierce engagements. Although the 3rd Infantry Division and other American troops were able to secure the beachhead, their advance was slower than expected due to the desperate resistance from their battled-tested German adversaries. The Germans launched several counterattacks that were defeated by American troops. Finally, on 23 March 1944, the 3rd Infantry Division attacked out of the Anzio Beachhead and brought the bloody campaign to a close.

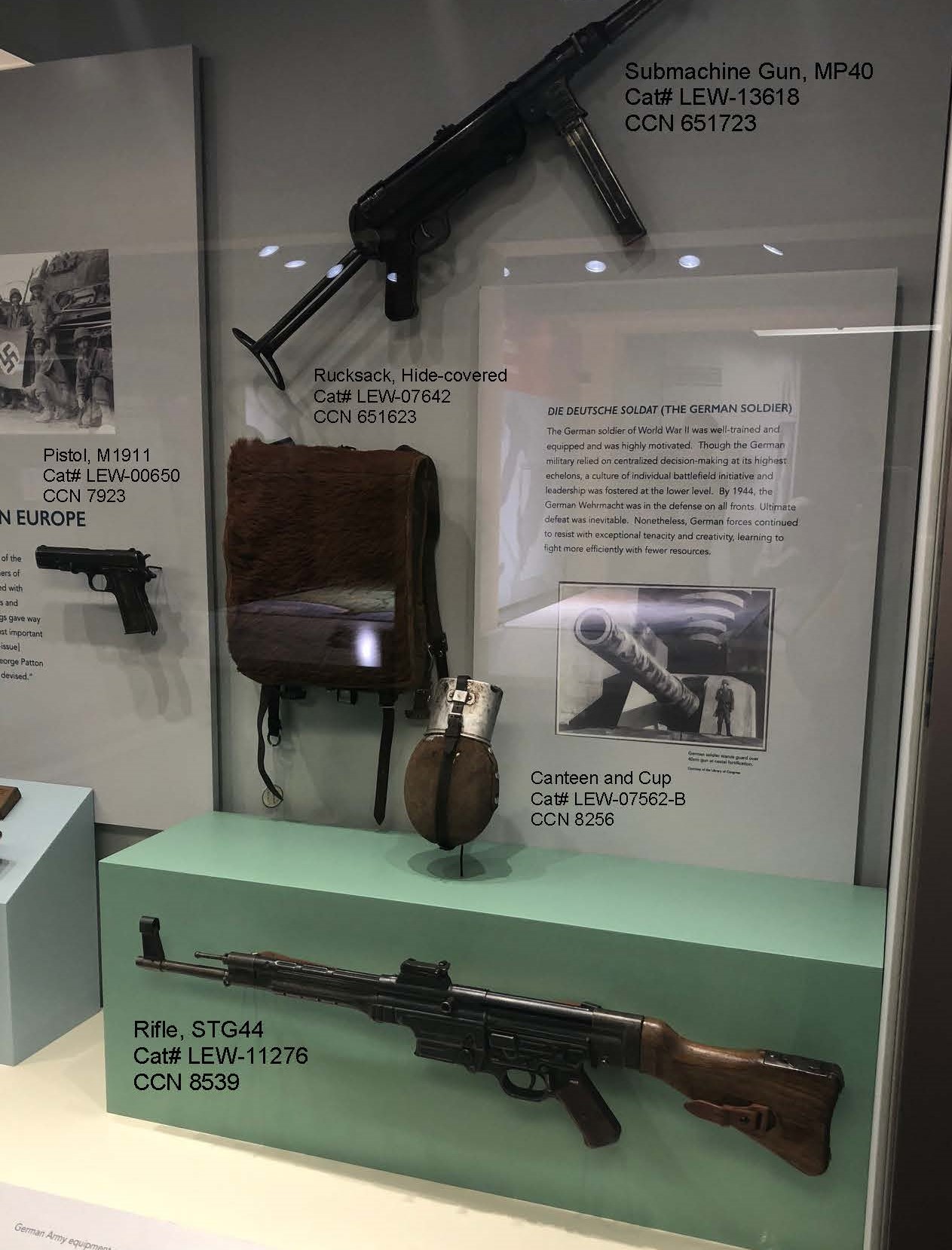

German Army Submachine Gun (LEW-13618)

German Army Hide-Covered Rucksack (LEW-07642)

German Army Canteen and Cup (LEW-7562)

German Army Select Fire Rifle (LEW-11276)

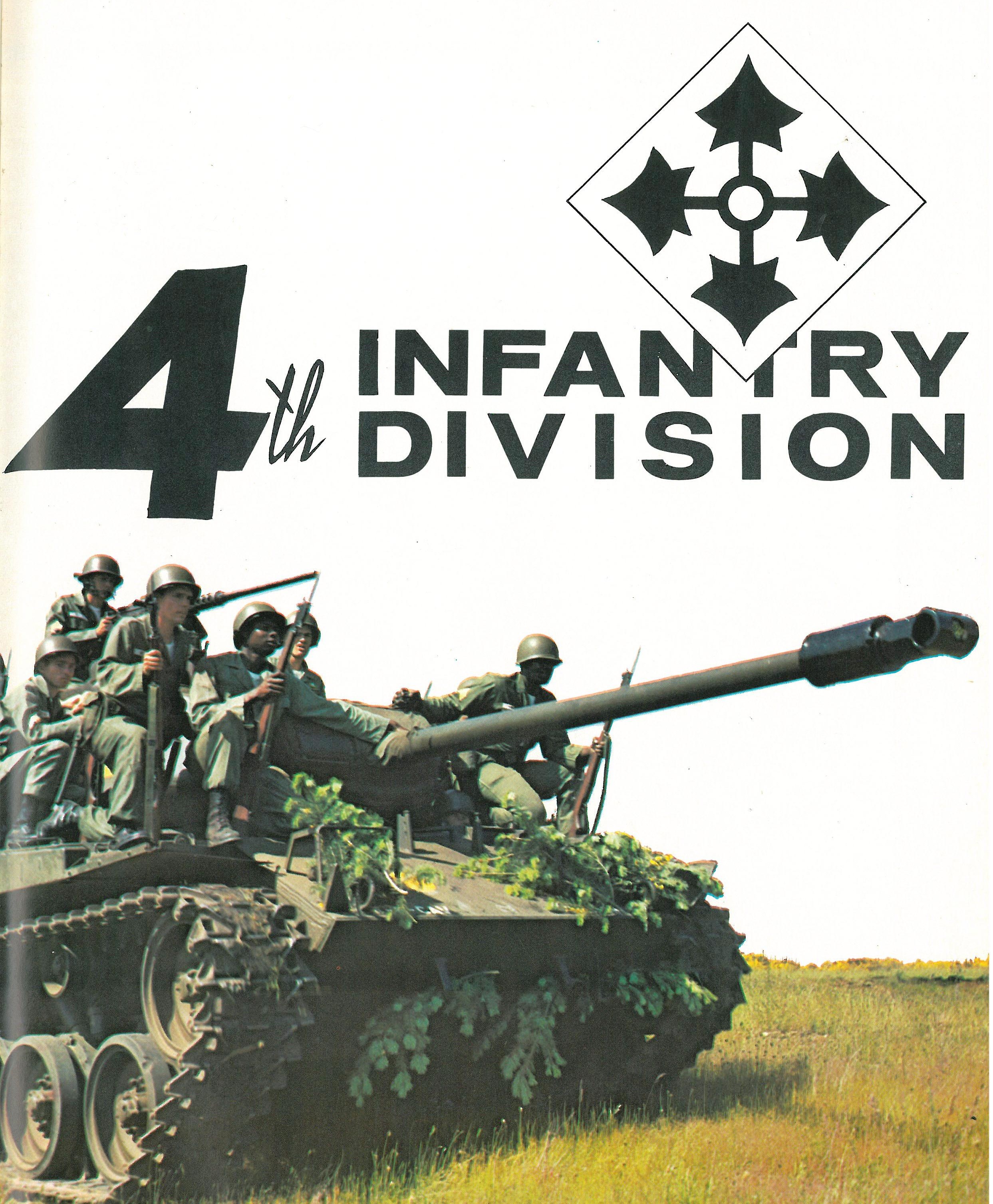

The 4th Infantry Division in Vietnam: “The Fighting Fourth”

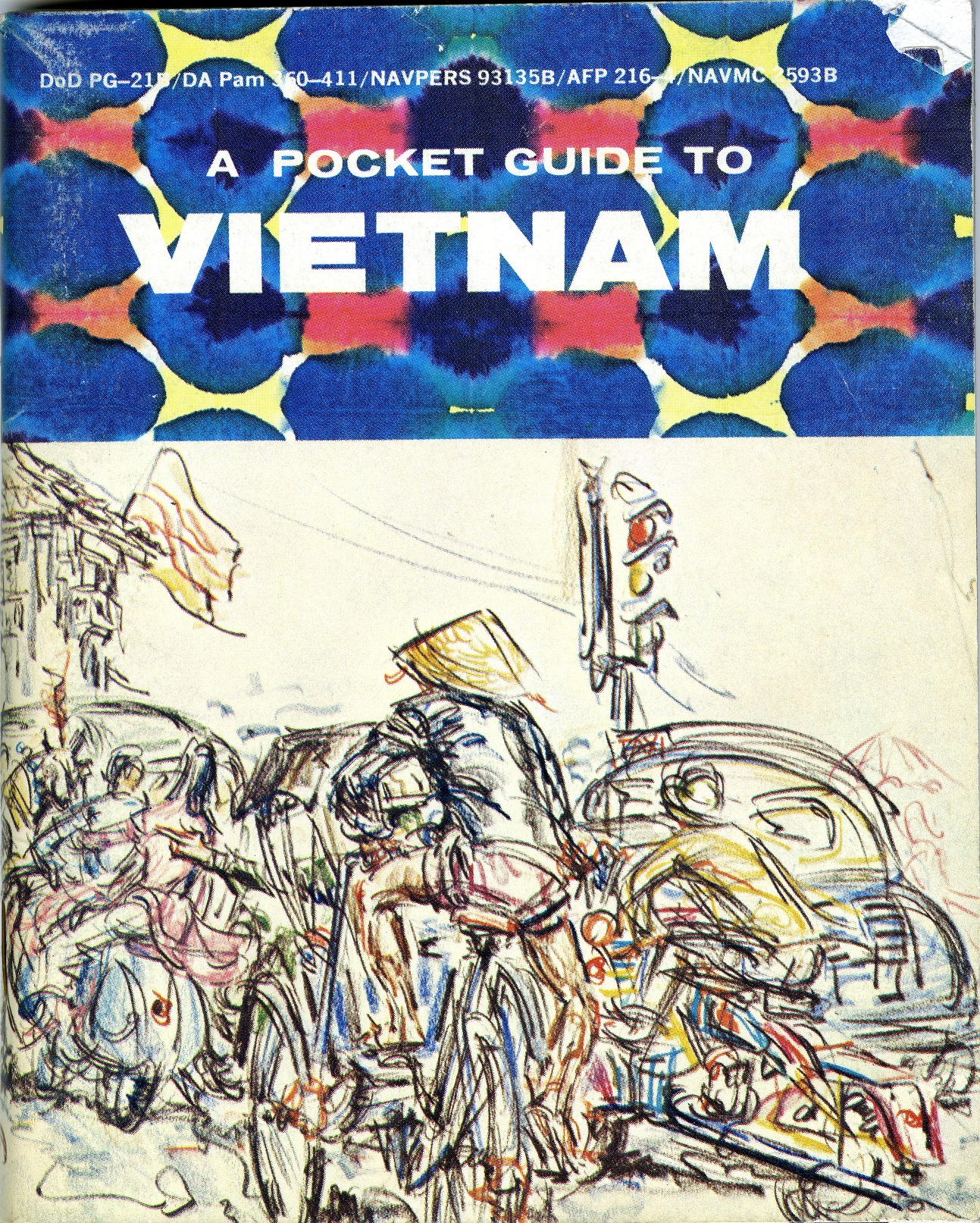

Following the bitter lessons of the Korean War, the United States Government was committed to fighting Communism in developing countries and supporting these countries through military assistance and economic development. In the mid-1960s, Vietnam became the focus of this strategy. Long held by France as a colony, Indo-China became an ever increasing hot spot for stemming the growth of Communism. After the defeat of French forces, American advisors were sent to Vietnam to help the South Vietnamese government fight the North Vietnamese Communists. This involvement escalated after the Gulf of Tonkin resolution and by 1965 American troops were fully committed to the Vietnam War.

The 4th Infantry Division served in Europe in both world wars. In 1956 the 4th arrived on Fort Lewis and began a ten year training period. As the war in Vietnam escalated, the 4th Infantry Division conducted maneuvers in the nearby Olympic rain forest in order to gain experience in a wet, jungle-like, area. In 1966, orders came for the Division to deploy to Vietnam. The Division arrived in theater in September and immediately conducted a major operation near the Cambodian border in Pleiku and Kontum Provinces. This operation lasted through December 1966.

The American Soldier in Vietnam

In 1966, the United States Training Center, Infantry, was activated at Fort Lewis. By 1972, over 302,000 men had completed infantry training. Many of these went on to serve in Vietnam. Fort Lewis also hosted an overseas replacement depot that processed over 1.5 million soldiers for service in Asia and the Pacific. Although American forces were never defeated in the field, political pressure and public dissatisfaction led the United States to gradually withdraw combat forces from Vietnam.

Vietnam-era training at Fort Lewis.

The Fighting Fourth

The infantryman of the 4th Infantry Division primarily served in the Western Central Highlands. The border with Cambodia was a particularly hostile region and the scene of many battles and skirmishes. The open and hilly nature of this region proved challenging while conducting operations against an aggressive enemy who could bring in equipment and reinforcements from Communist bases in Cambodia.

The 4th Infantry Division continued border surveillance operations in 1967. Throughout 1968 and into 1969 the Division conducted operations in the western highlands and engaged in fierce battles along the border. In June 1970 the Division entered Cambodia to attack North Vietnamese sanctuaries. The 4th Infantry Division is credited with serving 1,534 days in Vietnam.

General Westmoreland’s Pistol (LEW-00094)

U.S. Army M79 Grenade Launcher (LEW-13426)

U.S. Army M60 Machine Gun (LEW-13431)

U.S. Army M14 Rifle (LEW-07386)

U.S. Army Remington Pump-Action Combat Shotgun (LEW-02850)

U.S. Army M16 Rifle (LEW-03351)

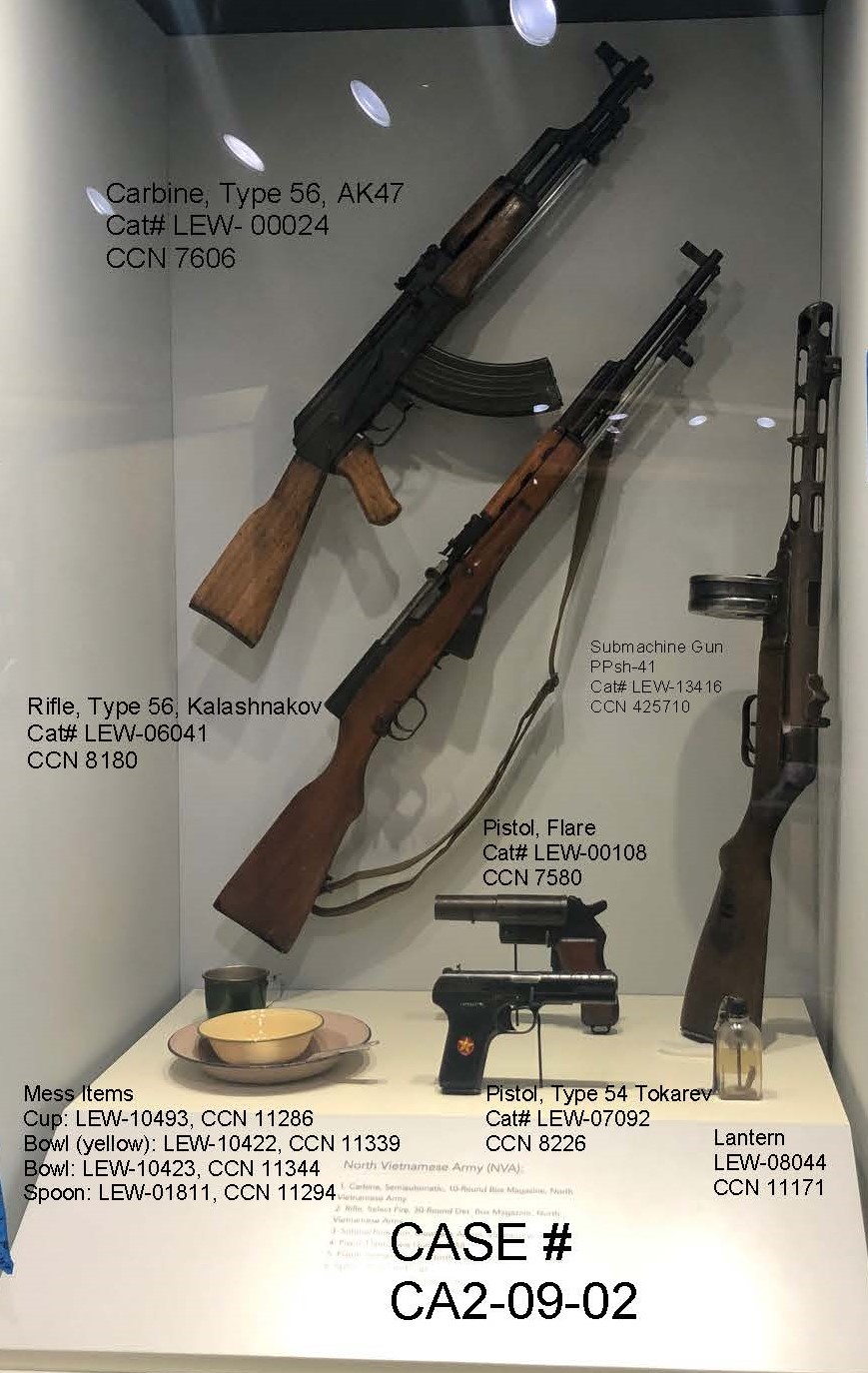

North Vietnamese Army Semi-Automatic (Type 56, AK47) Carbine with Folding Bayonet (LEW-00024)

North Vietnamese Army Kalashnakov (Type 56) Rifle (LEW-06041)

Vietnamese Submachine Gun circa 1944, used by the Viet Cong (LEW-13416)

North Vietnamese Army Flare Gun (LEW-00108)

North Vietnamese Army Semi-Automatic Pistol (LEW-07092)

Vietnamese Mess Kit, both North Vietnamese and Viet Cong (LEW-01811, LEW-10422, LEW-10423, LEW-10493)

South Vietnamese Field Lantern (LEW-08044)

WWII Prisoners of War at Fort Lewis

By Lewis Army Museum Volunteer, graduate student Emily White

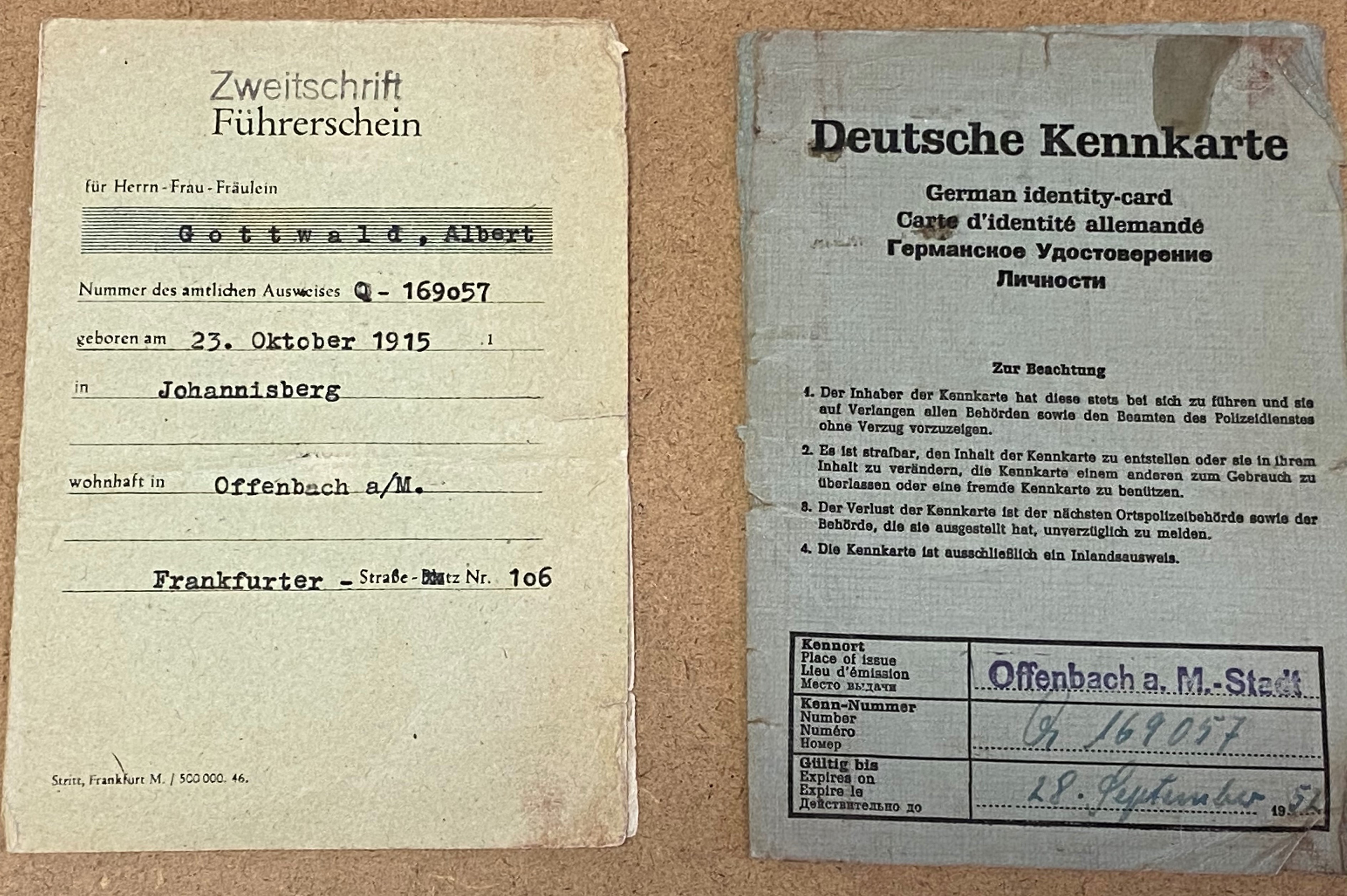

Prisoners of War were sent to Fort Lewis as early as 1942 when four Japanese, two Italians, and one German were held before being transferred. From that small beginning, the prison camp grew to five separate compounds on post, along with branch camps at Spokane, Walla Walla, Vancouver Barracks and Toppenish. The prisoner population consisted of mostly Germans during the time it was open.

Using the same WWII wooden barracks and administrative buildings occupied by American troops on post, the main camp was set up north of Gray Airfield in the area between 41st Division Drive and Pendleton Avenue. A separate compound was located about a mile away for troublesome prisoners and those that were Nazi Party members. Another compound was set up in a former CCC camp near the present-day Logistics Center.

The main camp was organized in three compounds, each surrounded by a barbed wire fence and ten guard towers. Each compound had four companies with four barracks, a mess hall, orderly and supply room, and a dayroom that was manned by German Prisoners. The compounds had a prisoner laundry, canteen, and barber shop. Two clinics served the camp and were staffed by German doctors and corpsmen under the supervision of an American medical officer.

The prisoners enjoyed a beer hall, carpenter shop, tailor shop, lecture hall with a library, an aquarium, and two theaters. One of the theaters was built by the prisoners for their theater group and orchestra. 80cents a day or $24 a month was earned for work unless docked 70 cents a day for disciplinary reasons or failure to work. The money could be spent at the canteens as well as deposits made into a prisoner welfare fund which was used to purchase recreational equipment and supplies. About 360 prisoners worked within the compounds, with the remainder of the enlisted men working on post at jobs such as clearing brush, sawing lumber, repairing clothing and equipment, and similar tasks. Others were sent out to work on various farms in the surrounding areas.

At one point the camp held approximately 5,200 prisoners. In the first year of operation the population of German soldiers were from the famed Afrika Corps. Germans captured in Italy, France, and Greece were brought to the camp as well. The last of the prisoners were sent back to Germany by July 1946, and the camp closed soon after. There are three German prisoners that died while in captivity, they are buried at the main post cemetery.

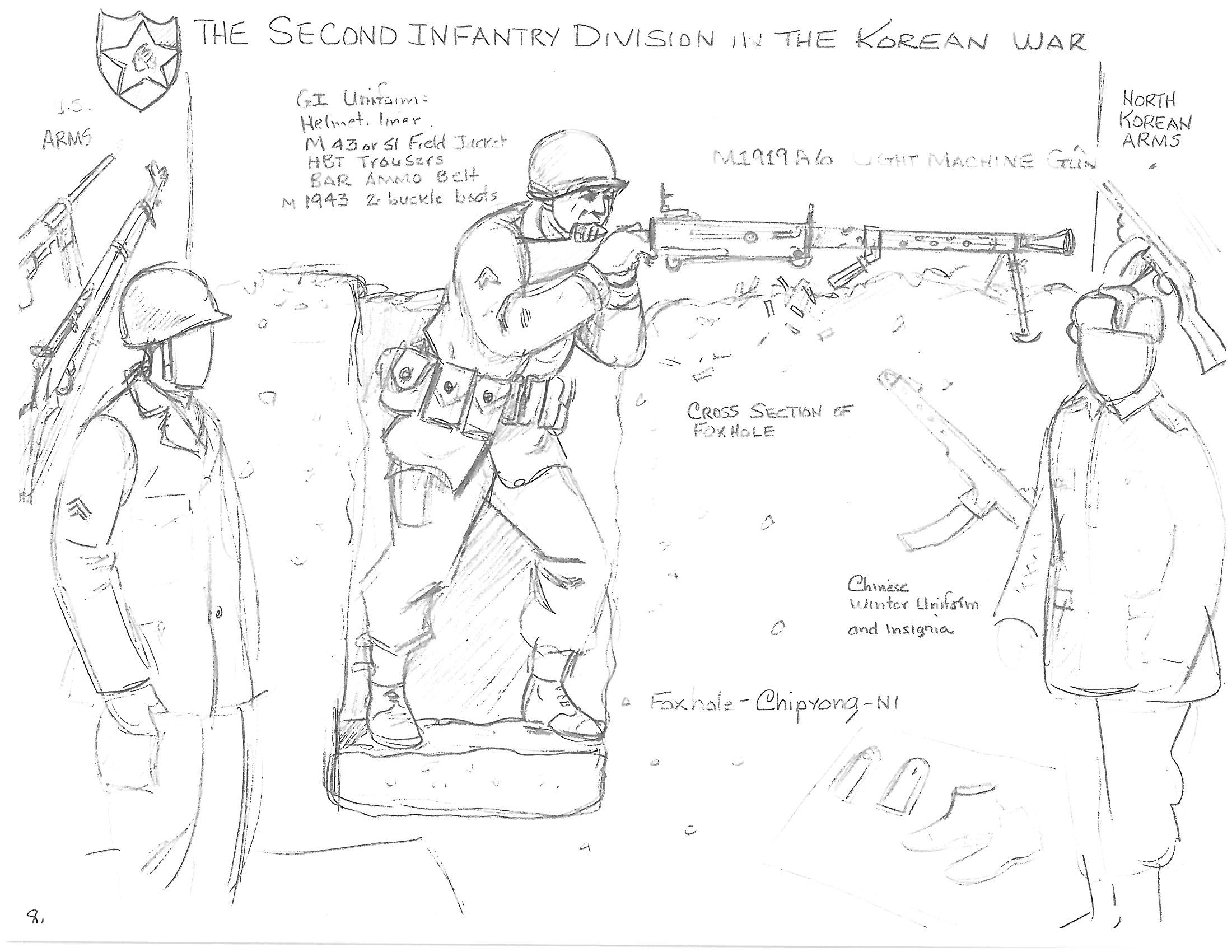

The Second Infantry Division in the Korean War

1950 – 1951 “Second To None”

After World War II Korea was divided, the north was controlled by a government that favored communism and the south was occupied by the United States after Japan’s surrender. The Korean War arose along the fault lines of the Cold War when the north attacked the south—with the support of China and the Soviet Union—in June 1950. The United Nations (UN) Security Council declared it an act of aggression and dispatched UN forces to South Korea’s defense. While a total of 21 countries would finally contribute to the action, the United States provided 88% of the military personnel and much of the equipment.

The Korean War ended with an armistice in 1953, which resulted in the creation of the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). While the DMZ is considered a buffer between North and South Korea, it acts as a de facto border. Hostilities remain between the two sides to this day.

The Second Infantry Division paid dearly for the freedom of South Korea. With 7,094 killed in action and 16,575 wounded, the Second Infantry Division had the highest casualties of any U.S. division in the Korean War.

Chipyong-Ni

In one of the most iconic battles of the Korean War, the 23d Infantry Regiment of the 2d Infantry Division, which included a battalion of French infantrymen, withstood ferocious Chinese attacks near Chipyong-ni, the 13th through the 15th of February 1951. The battle marked the apex of Chinese participation in the Korean War. Up until this time, the Chinese had a string of successful engagements. Although the Chinese made several penetrations of American lines during the battle, they were defeated by heroic counter-attacks. By the end of the second day of battle, the Chinese acknowledged their failure and retreated, giving the United Nations troops a significant boost in morale.

The American Soldier in the Korean War

Following the Allied victory in World War II, the U.S. Military went into a period of relative complacency. Although aware of a communist threat in Europe, less attention was paid to peace in Asia. As a result, the American forces stationed in South Korea were taken aback by the North Korean invasion in the summer of 1950. American troops stationed in Japan were ill-equipped to meet the threat and paid a costly price for their lack of readiness. Fortunately the 2nd Infantry Division was one of the Army’s most battle ready units and were immediately sent to Korea. Their arrival helped to halt the North Korean juggernaut and begin the process of driving the Communists back north.

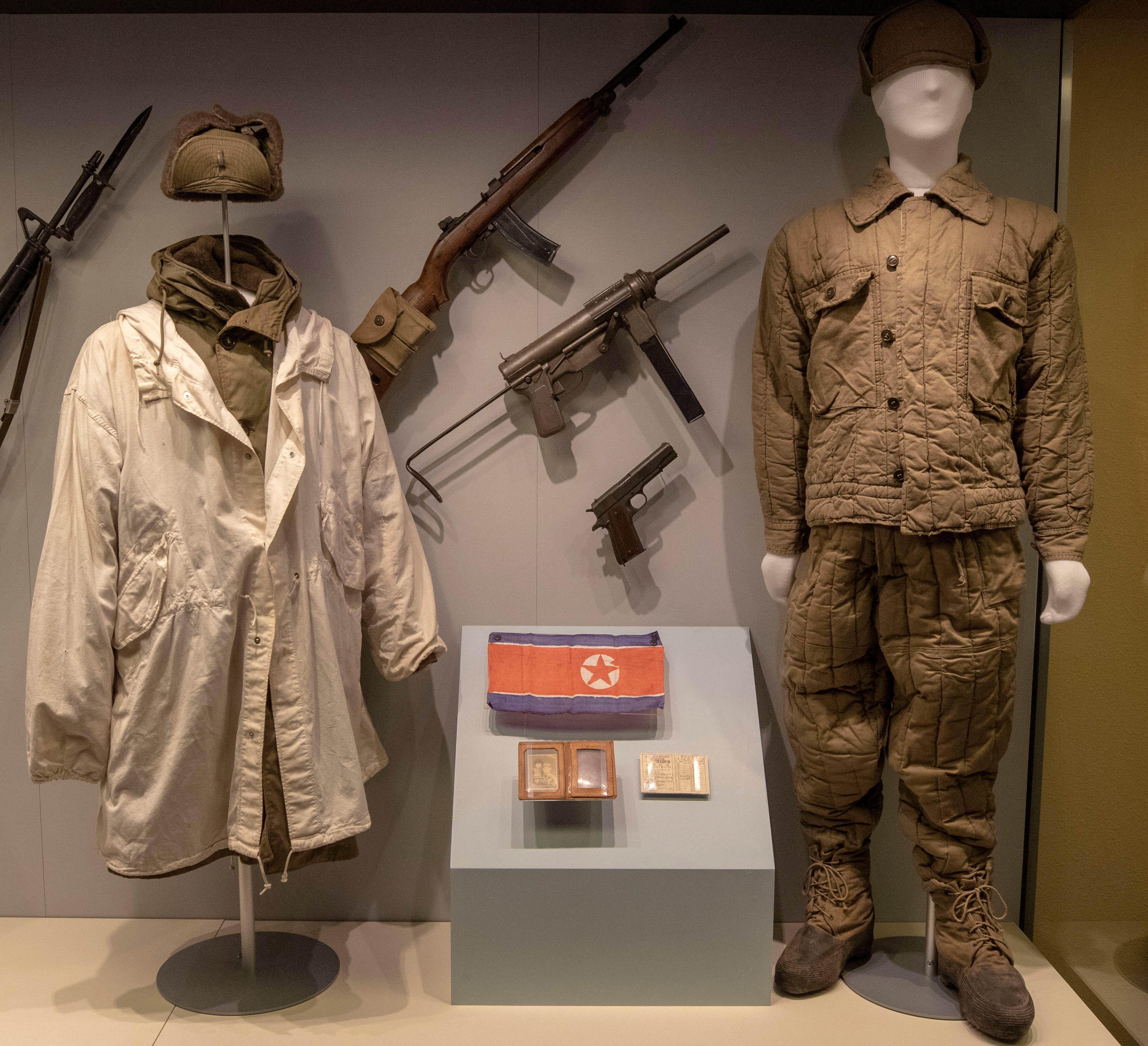

The soldiers of the Indianhead Division continued to be one of the most engaged American divisions throughout the Korean War. Most of the arms, uniforms, and equipment used by American troops and the other United Nations forces were provided by the United States military.

The American troops who deployed to Korea in the summer of 1950, were uniformed and armed much like the G.I. of World War II. As the war progressed specialized uniforms and equipment were developed to cope with the severe Korean winter conditions. The M2 Carbine and M3 “Grease Gun,” which could fire in a full automatic mode, were widely issued to combat the massive Communist attacks that often resulted in close-quarter fighting.

Communist Soldiers of the Korean War

During the early stages of the Korean War, the soldiers of North Korea were a formidable foe. Using arms and equipment provided by the Soviet Union and China, the North Korean Army was able to overwhelm the ill-prepared United Nations (UN) forces that opposed them. However, after the arrival of UN reinforcements, the North Koreans were forced to retreat back north until the Chinese Army intervened.

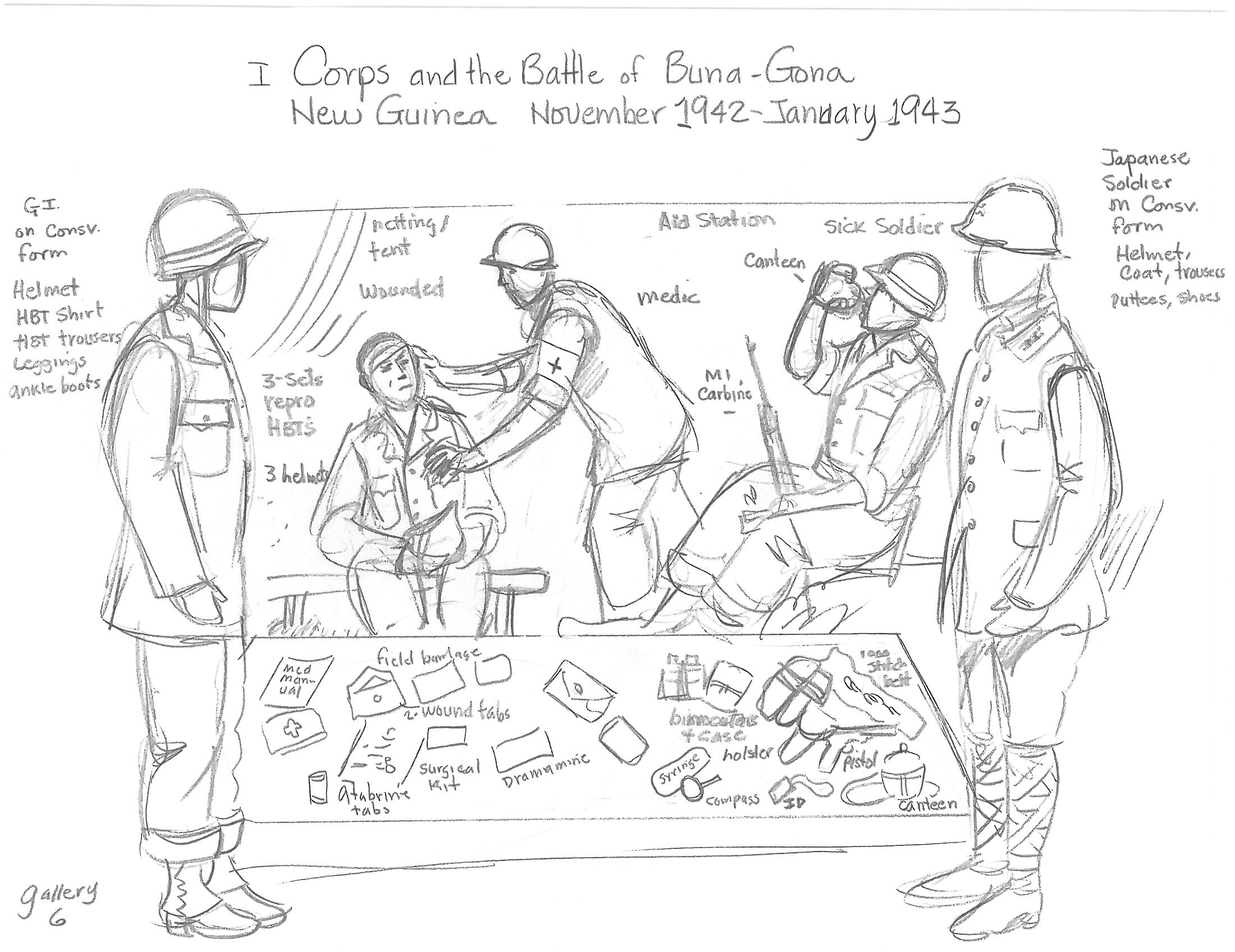

I Corps at Buna-Gona, Papua New Guinea, 1942-1943

“Take Buna, or do not Come Back Alive”

WWII in the Pacific

The United States initially remained neutral as World War II began, providing some aid to Britain, the Soviet Union and China through the Lend-Lease Act. As things heated up around the world, the US economic sanctions were brought against Japan, which outraged the Emperor and led ultimately to the bombing of Pearl Harbor. When the United States was attacked her citizens responded with a spirit of revenge seldom witnessed in our history. Recruiting stations were flooded with recruits eager to strike back at Japan.

I Corps

I Corps was organized during World War I and saw service on the Western Front. Although inactivated following the “Great War,” I Corps was reactivated on 1 November 1940 in response to the growing threat of war with Imperial Japan.

Between November 1942 and January 1944, I Corps troops were engaged in a series of hard fought battles. These battles were often fought at close range and to the death. On 3 January 1943, the Japanese forces were driven out of Buna, marking the first allied victory over the Japanese Army in World War II. However, heavy fighting and mopping up actions continued until the end of January.

New Guinea

In August 1942, I Corps deployed to Australia to plan the assault on Japanese forces in New Guinea. At the time of I Corps’ arrival on Papua, New Guinea in November 1942, the Japanese forces were at the height of their fighting power and they believed themselves invincible. General Douglas McArthur told I Corps’ Commanding General, Robert Eichelberger, “Bob, I want you to take Buna, or not come back alive.”

Major General (later Lt. Gen) Robert Eichelberger led both American and Australian troops in the Pacific. The soldiers of I Corps gave the United States one of its first victories of WWII in Buna. Following the New Guinea campaign, Eichelberger was promoted to lieutenant general and given command of the Eighth U.S. Army.

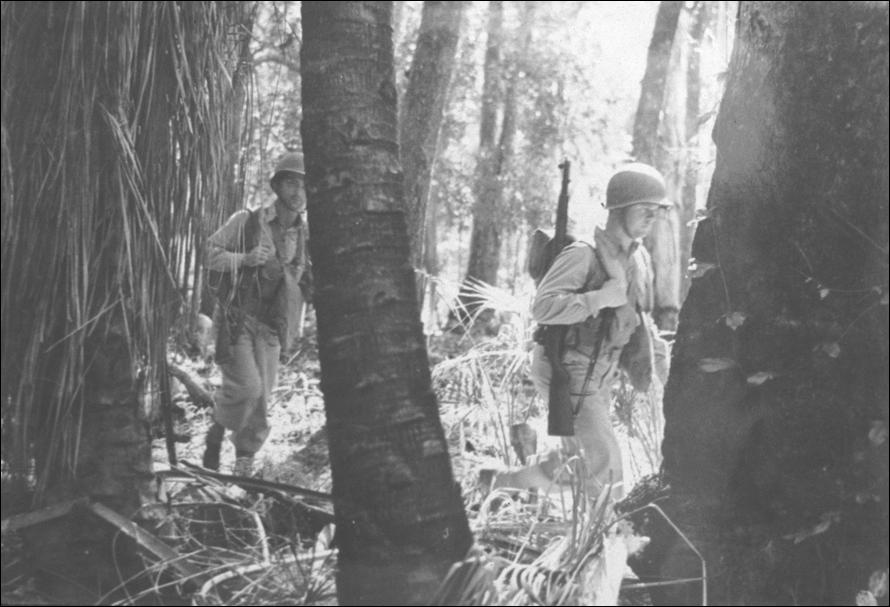

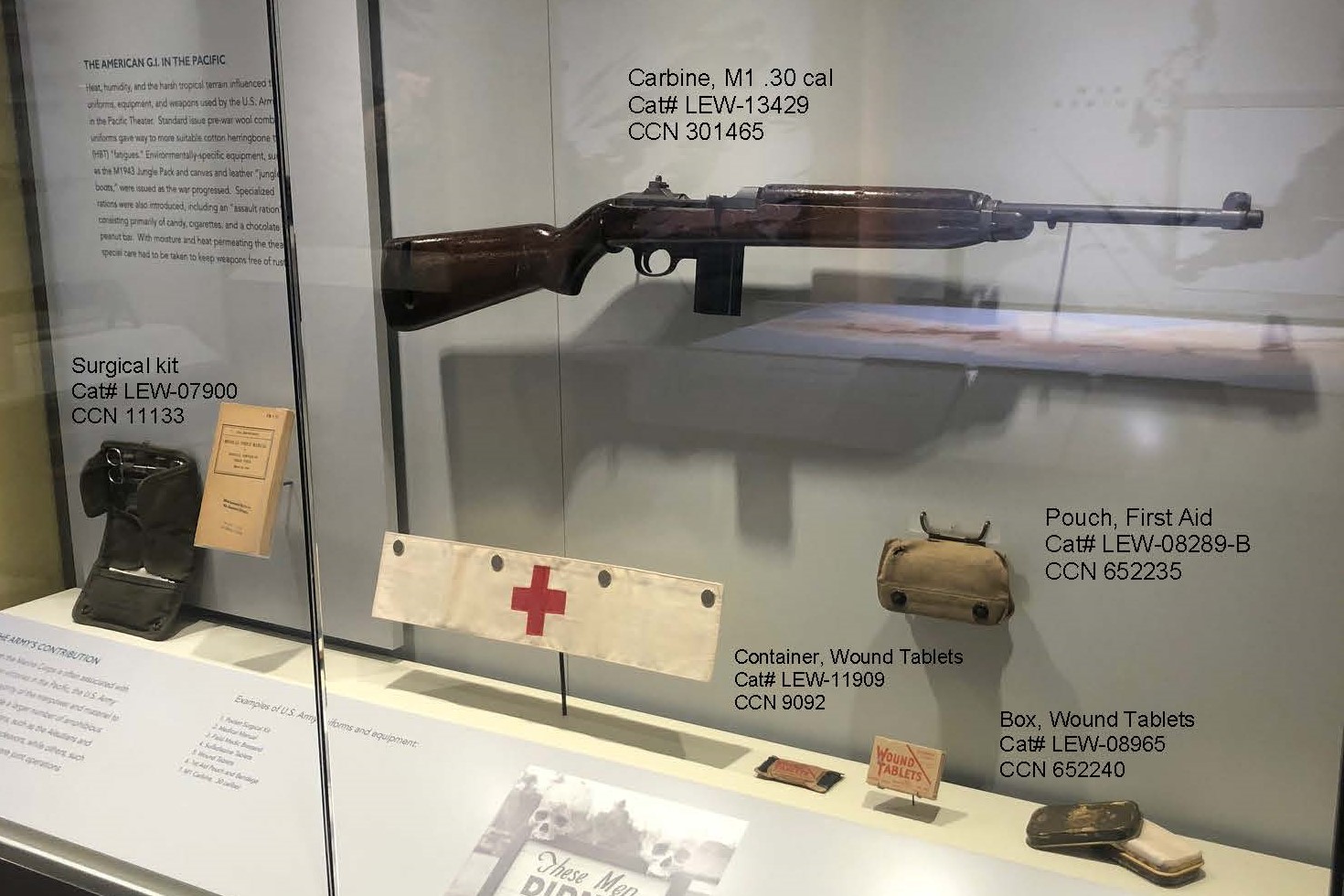

The American G.I. in the Pacific

While Japanese soldiers often thought themselves invincible, the Americans tended to underestimate the determination and fighting prowess of their foe. The American G.I. soon learned that he was fighting against a formidable enemy.

As the war progressed, the Japanese forces experienced dwindling manpower and supplies while the American soldier developed and employed ever-evolving battlefield tactics and were supplied with the most advanced arms and equipment in the world.

During the campaigns in the Pacific Theater of Operations, the tropical climate and associated diseases were as deadly an enemy as the Japanese forces. Malaria, typhoid, heat stroke and “jungle rot” took as big a toll on American troops as bullets and shells. Operating Field Medical Aid stations were one of I Corps’ biggest responsibilities. Modern medical care, both in prevention and treatment of tropical illness and battlefield casualties helped ensure an American victory.

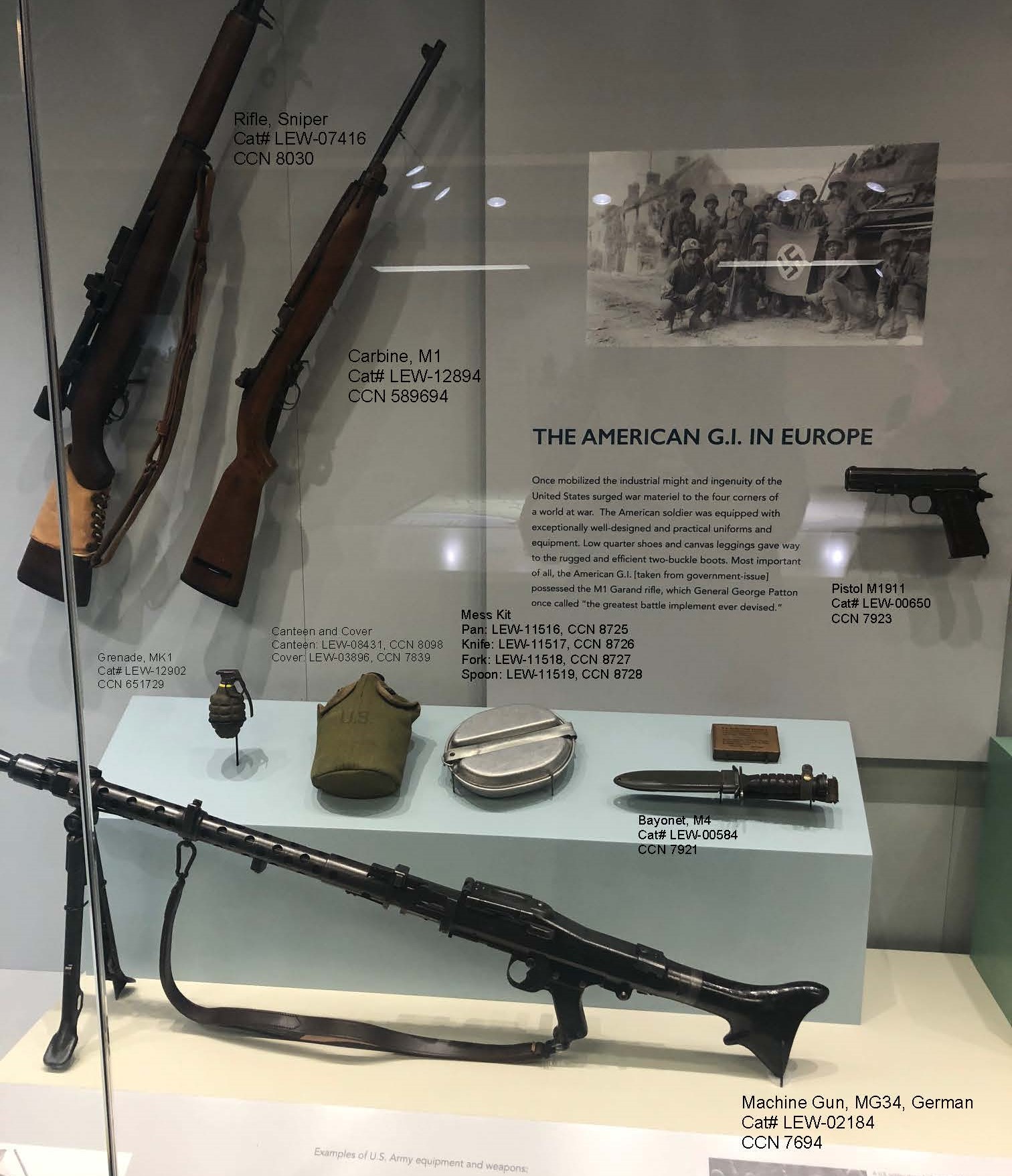

U.S. Army M1 .30 Caliber Carbine (LEW-12894)

U.S. Army Pocket Surgical Kit (LEW-07900)

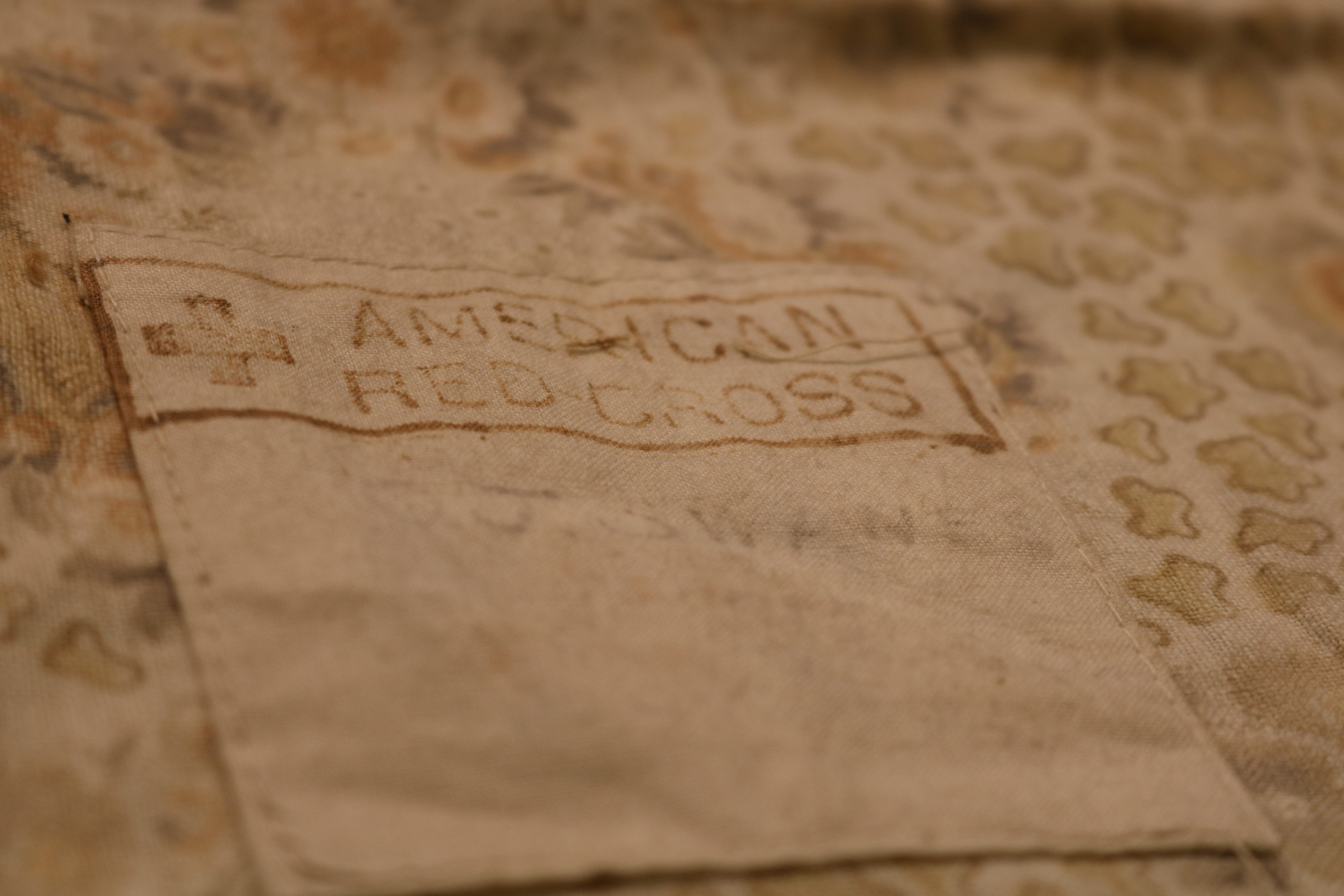

Red Cross Field Medic Brassard (No Catalog Number)

U.S. Army Sulfadiazine Wound Tablets (LEW-08965)

U.S. 1st Aid Pouch (LEW-08289-B)

U.S. Army Sulfadiazine Wound Tablets (LEW-11909)

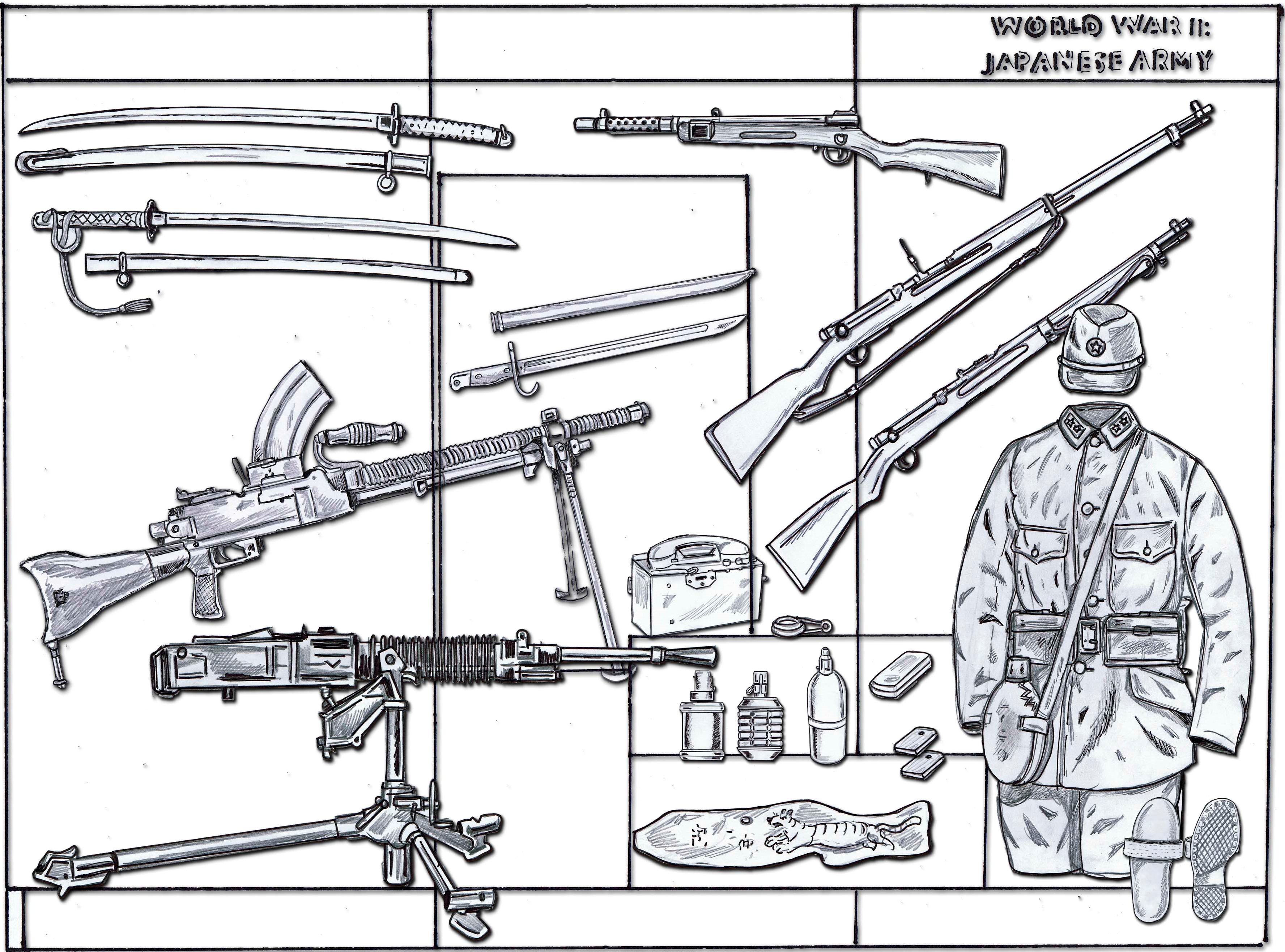

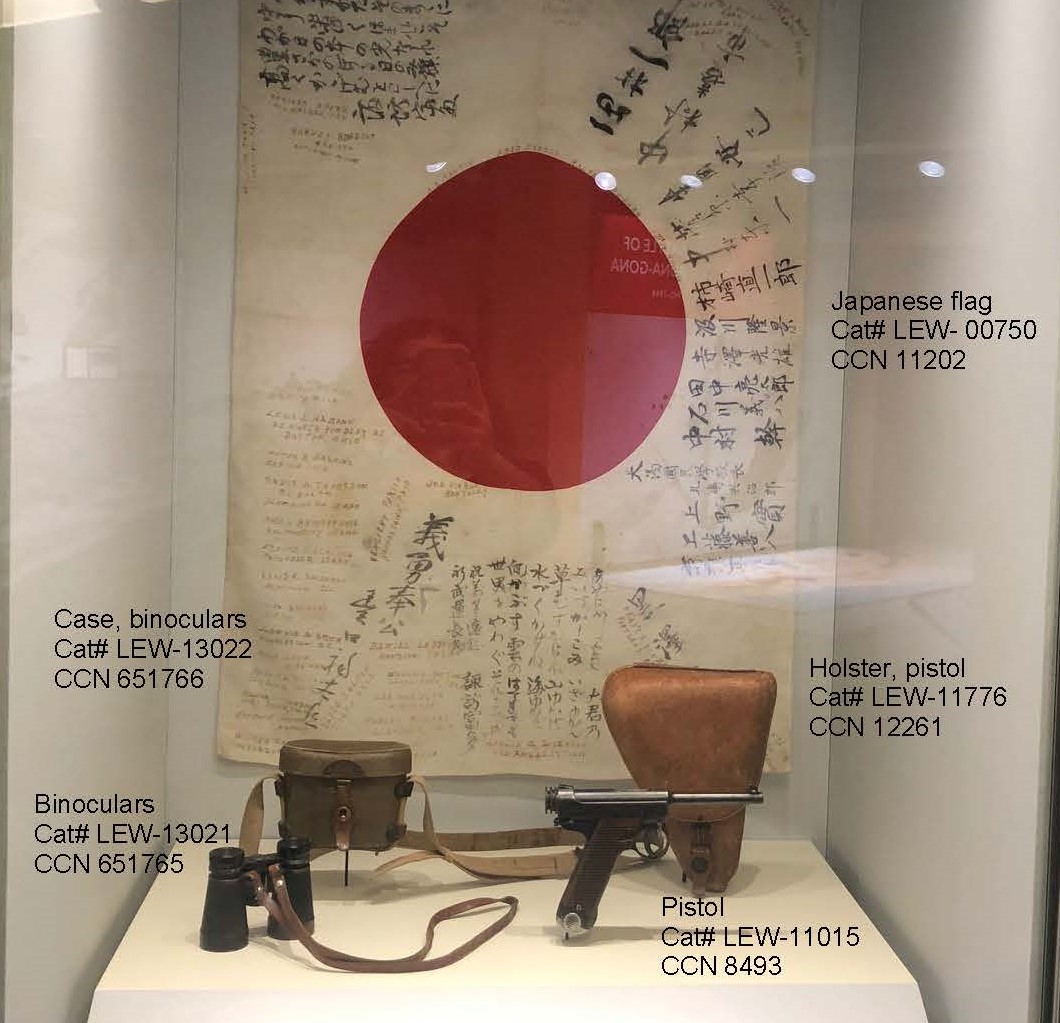

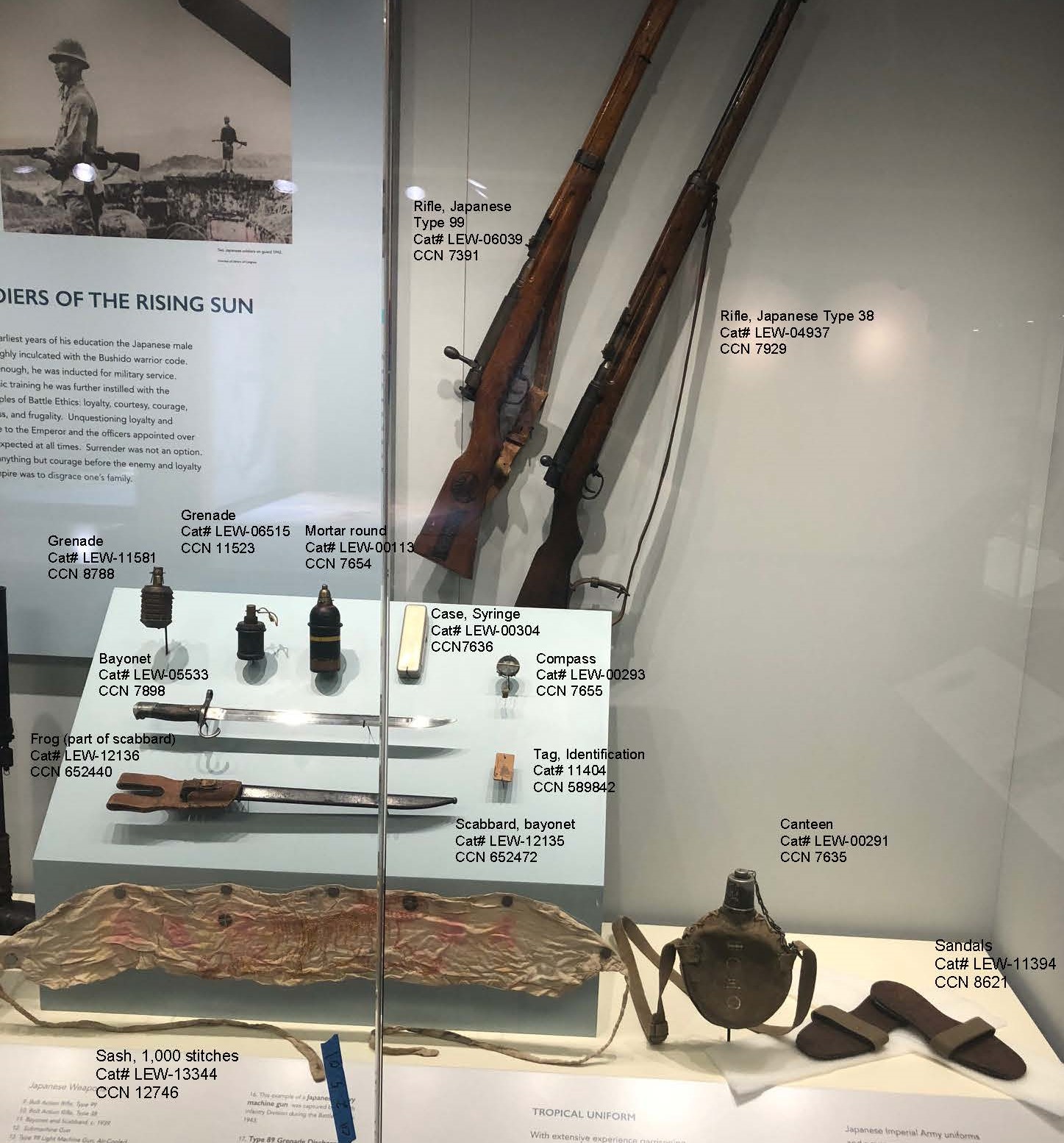

The Soldiers of the Rising Sun

At the time the United States entered the War in the Pacific, the Japanese Imperial war machine had reached its zenith. After victories in Manchuria, Korea, Indo-china and the Philippines, many a Japanese soldier believed he was invincible. Inspired by the warrior spirit, embodied in the code of Bushido, soldiers were aggressive on the attack and stubborn in defense. After the first American victories at Attu, New Guinea, and Guadalcanal, the Japanese Army was put in a defensive position. With dwindling manpower and resources, the Japanese military could not match their enemies in terms of weapons, medical care, or manpower. In spite of their personal courage and dedication to the Land of the Rising Sun, the soldiers of the Army of Imperial Japan were ultimately defeated.

Japanese Flag with Signatures of U.S. Soldiers. Captured by a 41st Infantry Division soldier in the Pacific Theater, circa 1944 (LEW-00750).

Japanese Army Field Binoculars and Case (LEW-13021 and LEW-13022)

Japanese Army Pistol Holster (LEW-11776)

Japanese Semiautomatic Type 14 Pistol (LEW-11015)

Japanese Army Bolt Action Rifle, Type 99 (LEW-06039)

Japanese Army Bolt Action Rifle, Type 38 (LEW-04937)

Japanese Fragmentation Grenades (LEW-06515 and LEW-11581)

Japanese Mortar Round (LEW-00113)

Japanese Army Syringe Kit circa 1942 (LEW-003034)

Japanese Army Wooden Identification Tag, circa 1942 (LEW-11404)

Japanese Army Compass (LEW-00293)

Japanese Army Bayonet and Scabbard, circa 1939 (LEW-11777 and 11778)

Japanese senninbari, sash (or belt) of 1,000 stitches (LEW-13344)

Japanese Army Water Canteen, circa 1943 (LEW-00291)

Japanese Army Barracks Sandals (LEW-11394)

Japanese Army Officer’s Daito Sword and Scabbard (LEW-13287)

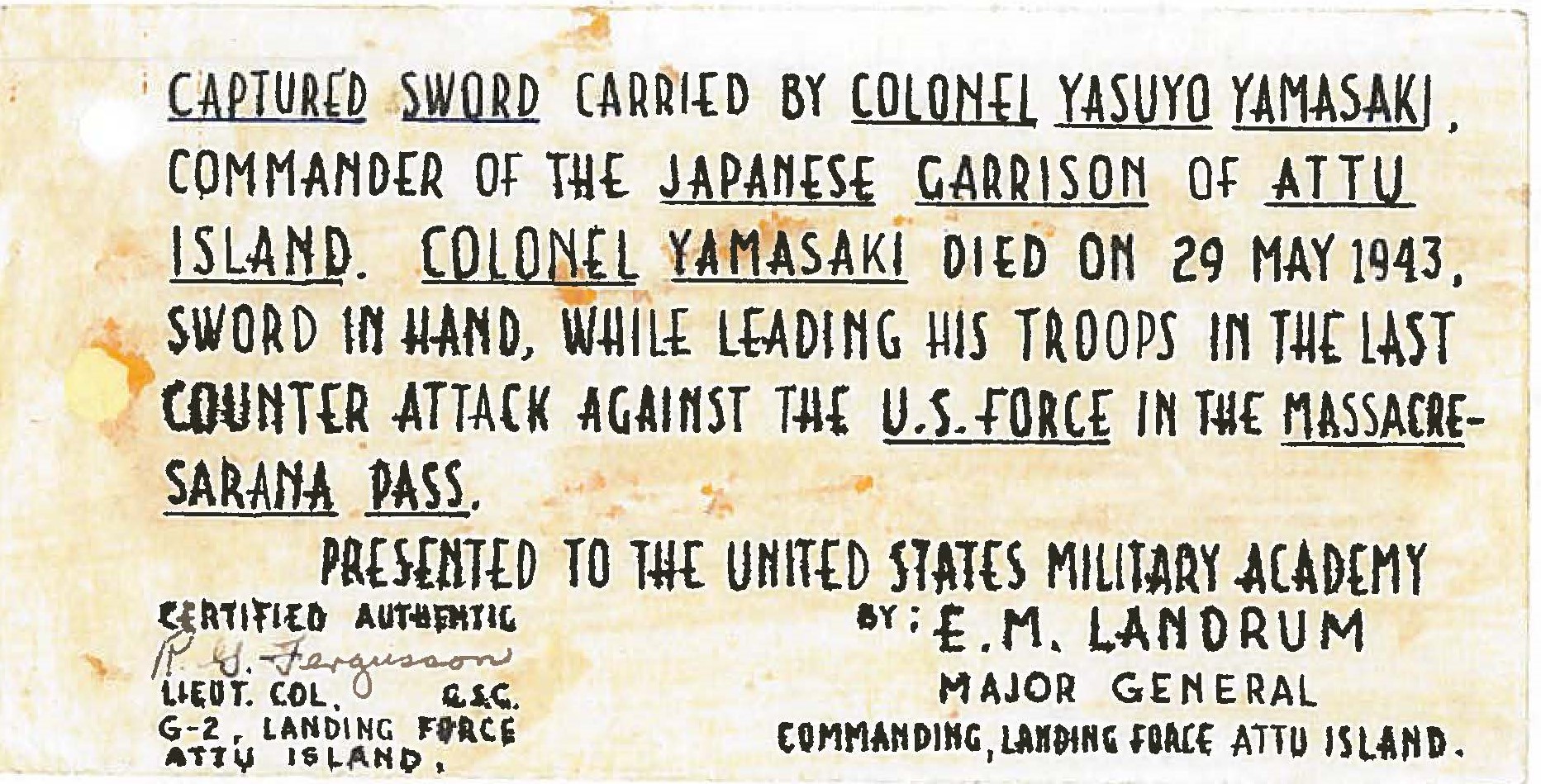

Japanese Army Officer’s Katana Sword, Knot and Scabbard on loan from West Point Museum (Cat #s 02143.1, 02143.2, 02143.3)

Japanese Type 99 Light Machine Gun (LEW-00095)

Japanese Army Projector “knee mortar” (LEW-02851)

Japanese Army Type 92 Machine Gun (LEW-13520)

Japanese Army Field Telephone (LEW-11696)

The 91st Division in WWI

The assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary in June 1914 ignited the spark of war in a Europe already rocked by forces of globalization, revolution and rapid technological change. World War I was meant to conclude swiftly, but the European arms race had created weapons and machines that changed forever the nature of war. The U.S. initially vowed to remain neutral—but German attacks on merchant vessels and attempts to form a secret alliance with Mexico ultimately led to President Wilson’s declaration of war in 1917. The U.S. Army was sent to reinforce the Western Front, where in September 1918, it prepared for the final decisive battles of the War.

The 91st “Wild West” Division in the Great War, 1917-1918

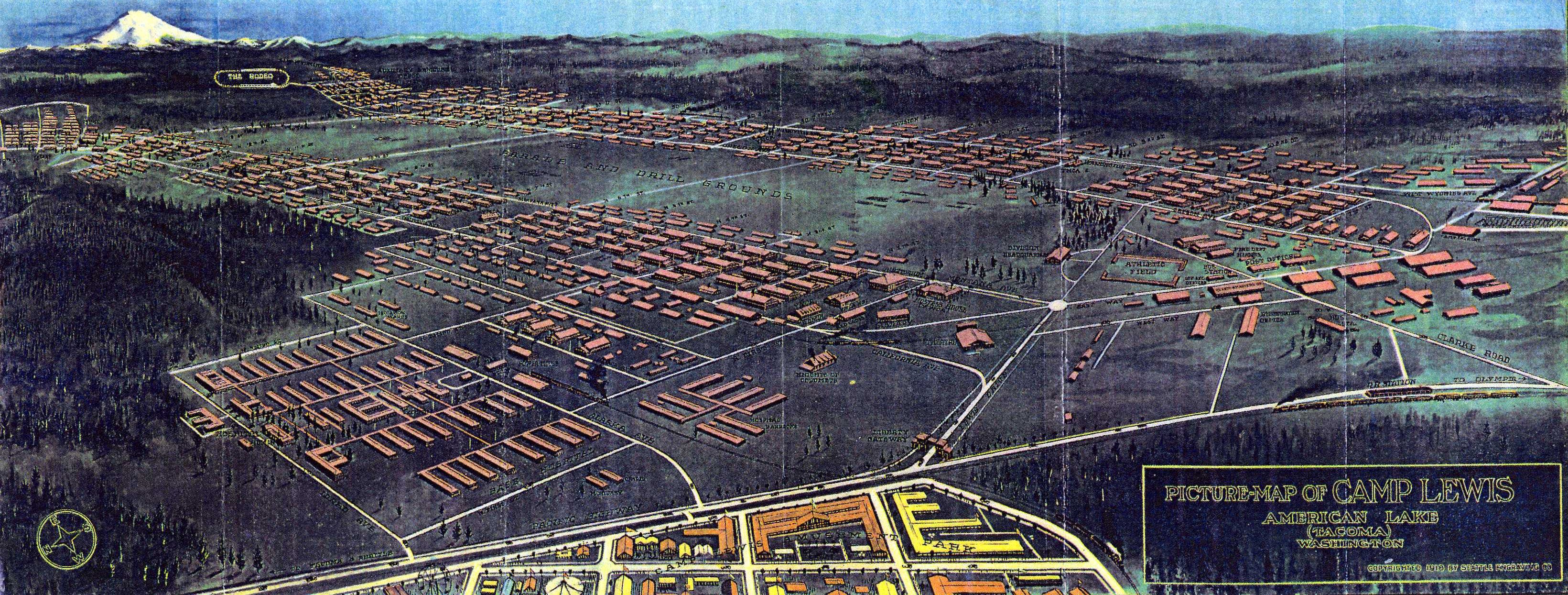

When the United States entered the First World War, in April 1917, Congress approved the establishment of sixteen new cantonments to train the new National Army. The largest Army cantonment in the United States was constructed on the Nisqually Prairie in Pierce County, Washington, on land donated by the local citizens. Originally called Camp American Lake, in July 1917, it was formally named Camp Lewis, in honor of famed explorer, Captain Meriwether Lewis.

In September 1917, the first recruits arrived, by August, the new enlistees and conscripts, were formed into the nucleus of the 91st Division. The men were primarily from the western states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, and northern California. Their frontier western origins led to the nickname of the “Wild West Division” and they adopted the battle cry of “Powder River, let ‘er buck.” The 91st trained at Camp Lewis, often assisted by veteran allied officers from England and France. Trenches and various fortifications, found on the Western Front, added to the realistic training conducted on Camp Lewis.

Powder River, Let ‘er Buck.

In June 1918, the 91st Division left Camp Lewis, bound for the Western Front. When the division arrived in France, in July 1918, the Europeans were fascinated with the “cowboys” from the Wild West. In August, the 91st Division saw their first action in the St. Mihiel Offensive. The division was then committed to the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the largest allied operation of the war. In September, the Wild West Division earned it “spurs” by smashing through three lines of German defenses, defeating an enemy counterattack, and inflicting a devastating blow to the First Guard Division of the German Army. In mid-October, the 91st Division was sent from the Argonne forest to Belgium to assist our allies in the Ypres-Lys offensive. The men of the 91st Division helped push the German Army east across the Escaut River shortly before the Armistice ended the fighting on 11 November 1918. In 1919, the 91st Division returned to the United States and was inactivated at the Presidio of San Francisco.

Fighting in the Argonne Forest

The men of the 91st Division saw some of the heaviest fighting of the war while advancing through the Argonne Forest in September and early October 1918. Here the men of the Division claimed that they earned a reputation as “Shock Troops.” They overran a number of German machine guns positions and defeated am enemy counterattack. As a result, they were pulled out of the Argonne-Argonne offensive and sent to Belgium to participate in the stalled Ypres-Lys offensive. Their courage and determination helped bring about the Allied victory on 11 November 1918.

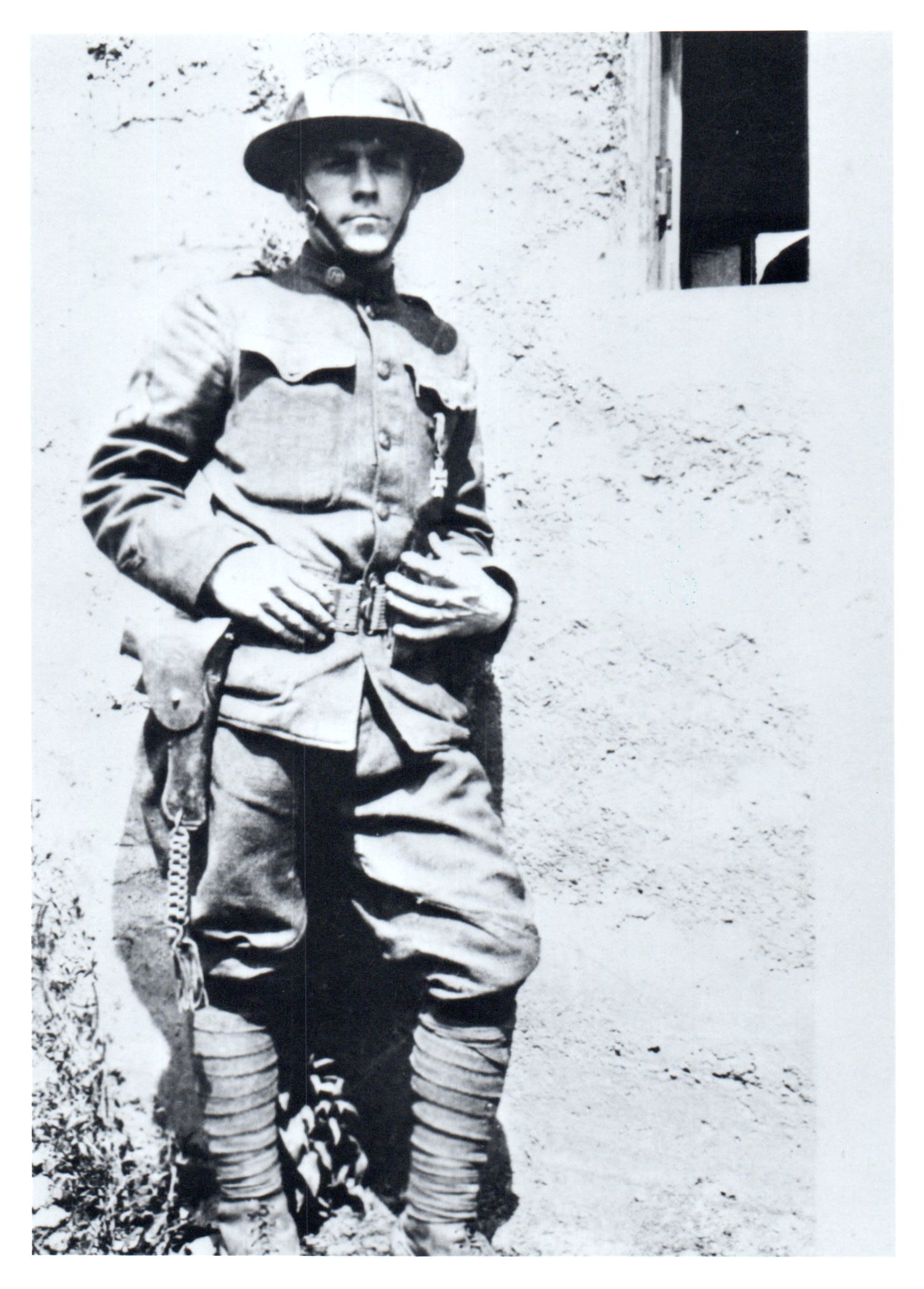

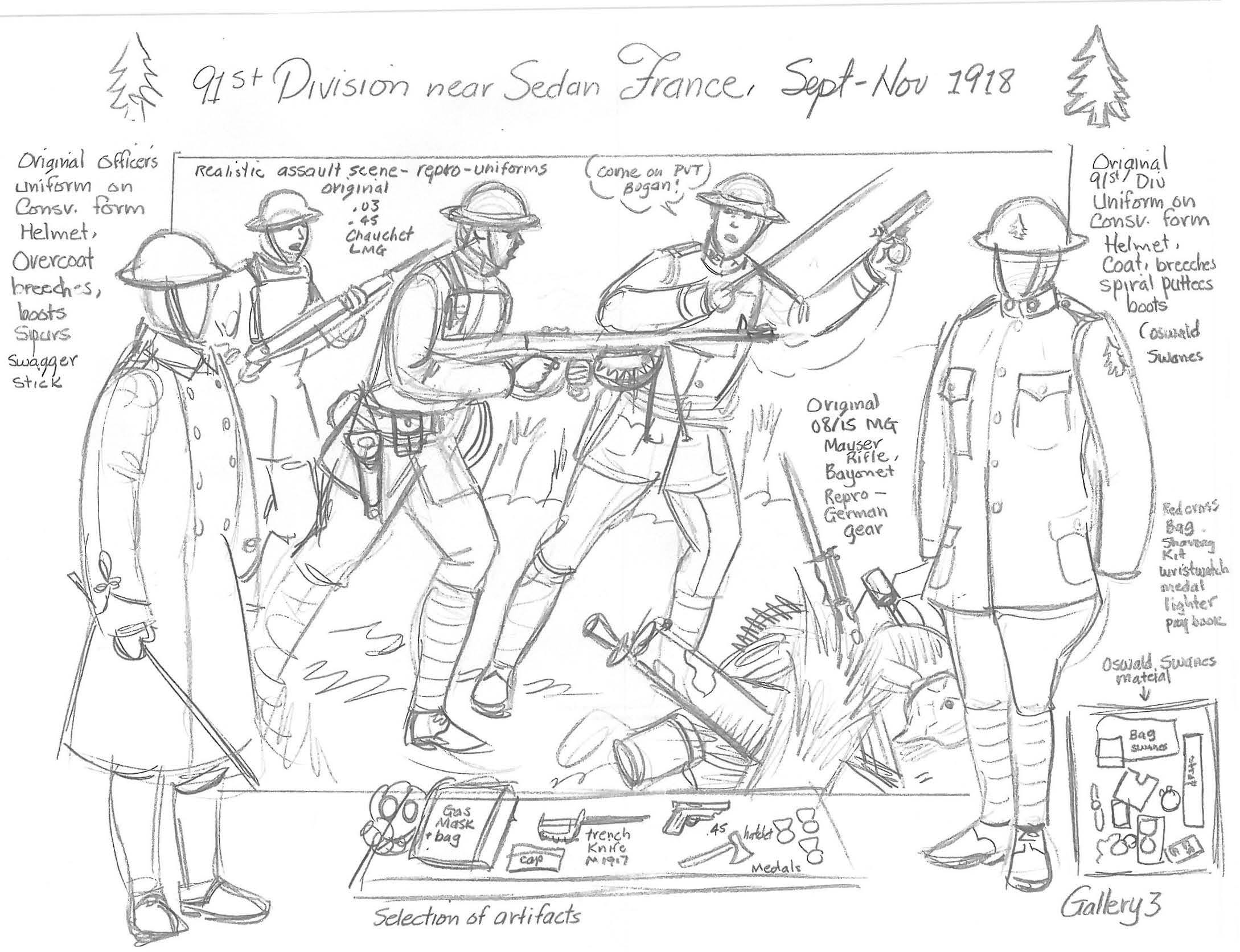

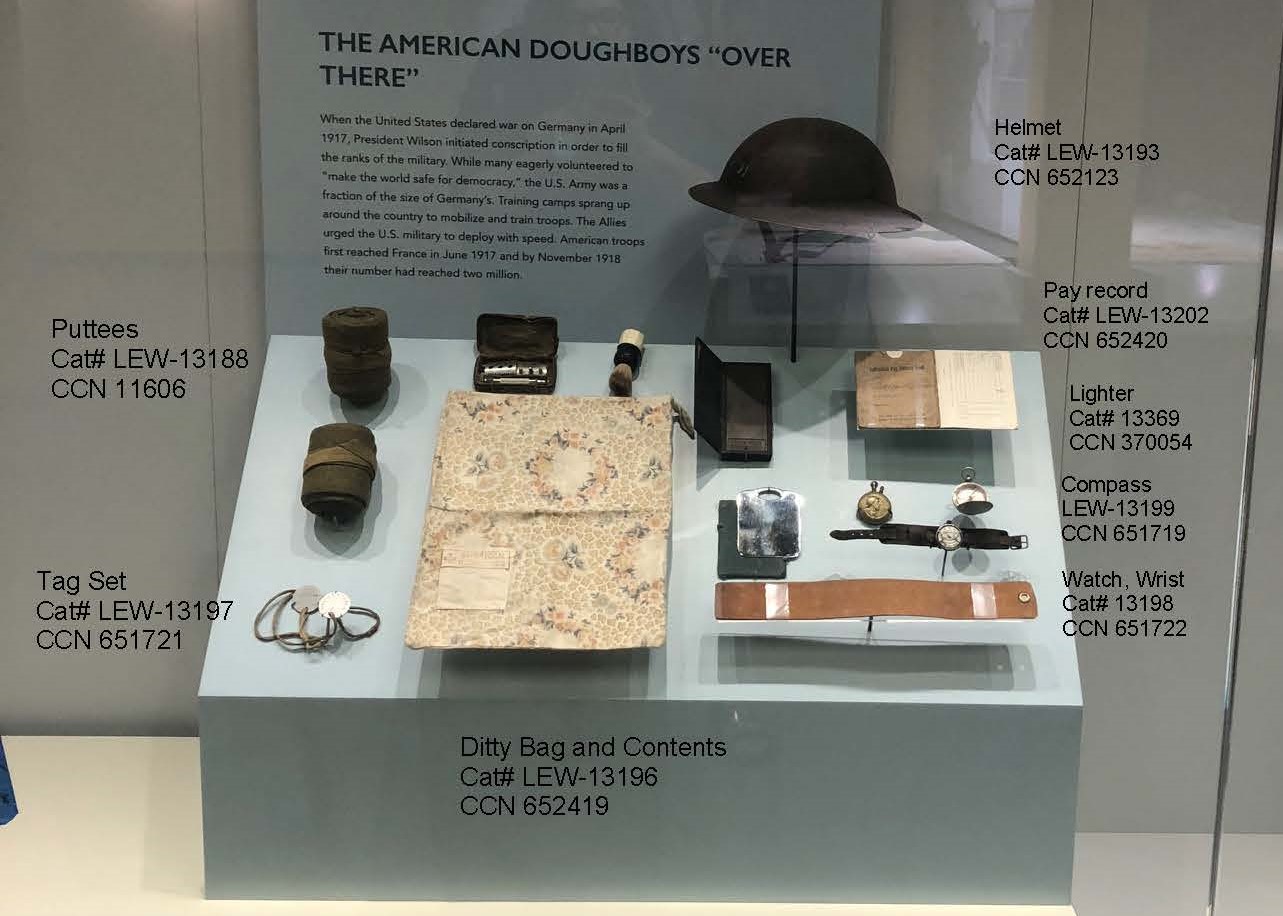

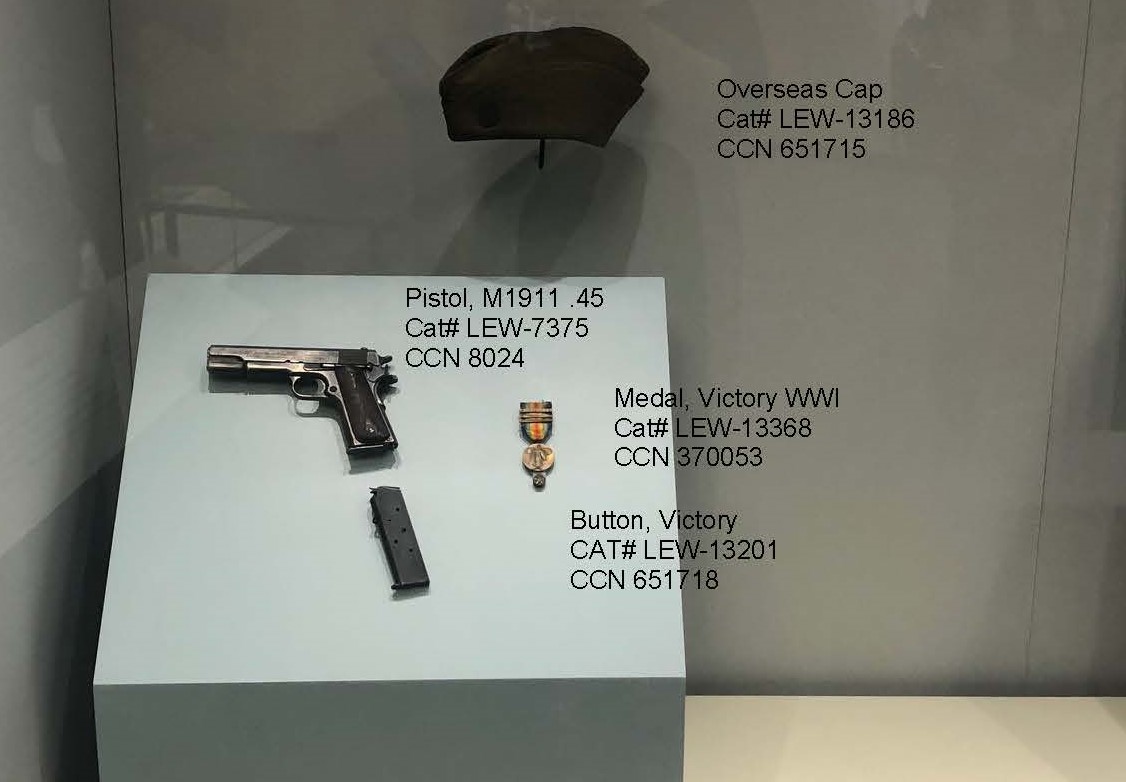

Soldier Profile: Oswald J. Swanes

One of the young men who joined the 91st Division at Camp Lewis in 1918, was Oswald J. Swanes. Serving in the 347th Machine Gun Battalion of the 91st Division, Swanes saw considerable action and his experiences in World War I would prove central to his future life. He returned to Tacoma after the war, ran a fish business, and was active in local veteran’s activities.

All artifacts (except M1911 Pistol), donated by Oswald J. Swanes.

U.S. M1917 steel helmet with 91st Division “Pine Tree” insignia (LEW-13193)

Overseas Cap (LEW-13186)

WWI Victory Medal (LEW-13368)

Red Cross Ditty Bag and contents (LEW-13196)

Cotton print ditty bag issued by the American Red Cross. Bag came with the following items: one shaving brush (brown and white plastic with boar bristle brush); one razor kit in box; one polished steel mirror in dark green cover; one “Fraz Swaty” hone in black wood box; one pig skin strap with eyelet; one small glass vial, unopened, with lighter flints inside.

U.S. Army Identification Tags (LEW-13197)

U.S. Army Pocket Compass (LEW-13199)

U.S. Army Wristwatch (LEW-13198)

U.S. Army Pay Record Book (LEW-13202)

U.S. Army Spiral Puttees (LEW-13188)

Razor Strop (From ditty bag)